- A majority of Victorians oppose a treaty between the Victorian Government and Victorian Aboriginal groups.

- In a forced-choice scenario, 52% of Victorians oppose a treaty, while 48% support. This closely resembles the 2023 Voice referendum, where 54% of Victorians opposed the Voice, while 46% supported. When Victorians are given the option to remain undecided, 37% of Victorians support a treaty between the state and Aboriginal groups, 42% oppose, and 21% are unsure.

- The demographic groups that support and oppose treaty reflect the same polling trends of supporters and opponents of the 2023 referendum. Around four in five voters hold the same view on treaty as they did on the Voice, indicating stable underlying attitudes.

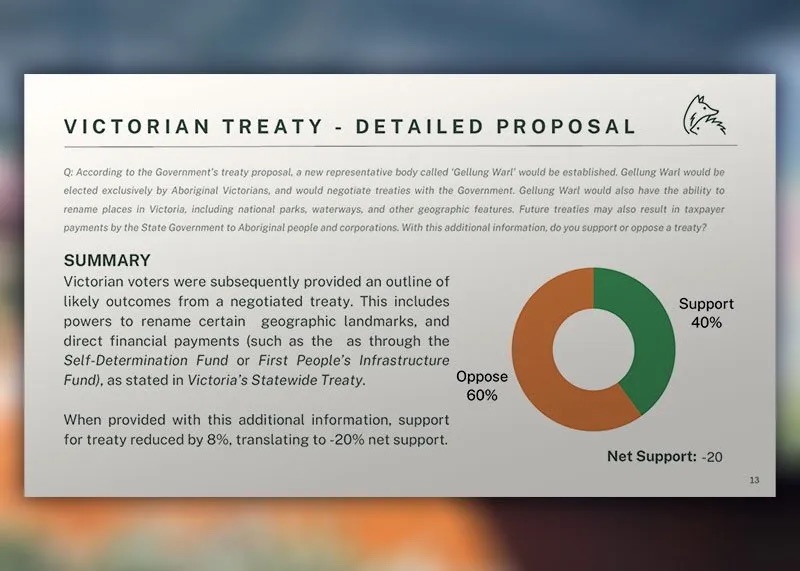

- Support for treaty declines from 48% to 40% when respondents are informed of the likely outcomes of a treaty. Opposition commensurately rises from 52% to 60%.

- When shown the Statewide Treaty Bill 2025’s definition of treaty, support falls slightly further to 39%, and opposition rises to 61%.

- Just over half of Victorians oppose ‘Gellung Warl’ being independent from the direction or control of the Victorian Government, with the remaining respondents evenly split between supporting its independence, and being undecided.

Poll: The Victorian Treaty what Victorian’s really think

Only serves to highlight how pathetic Jacinta Allan is a disgrace to the state and the nation. How dare she put tbis in place when we don’t want it.

She has become a dictator.

Jacinta Allan is a communist.

Helen is trying to become dictator instead. All heil Helen. That is who she runs with.

I am no dictator you have me confused with Jacinta Allan.

Victorian government has rammed through the Upper House last night a treaty that pretty much no one wanted.

If this Treaty truly represents all Victorians, the government should have the courage to put it to a vote. Until then, it remains a deal negotiated behind closed doors, driven by ideology, not equality.

Victoria needs unity, fairness and accountability — not another expensive symbol that divides people by race. The path to reconciliation lies in shared purpose, not separate privilege.

It has been hailed as a “once-in-a-century milestone.” But behind the warm words of reconciliation lies a troubling reality: the Treaty threatens to divide Victorians by race, undermine democracy, and saddle taxpayers with yet another expensive layer of bureaucracy.

For decades, Australians have worked to close the gap through education, health and housing programs. Billions have been spent, and progress has been made. But instead of focusing on what unites us, the Treaty process enshrines the idea that one group of Victorians should be treated differently from everyone else — not because of citizenship or need, but because of ancestry.

The first and most obvious problem is division. The Treaty’s core premise is that First Peoples hold a separate, unceded sovereignty that must be recognised in law. That might sound symbolic, but in practice it means creating a dual system of representation and influence — one for Indigenous Victorians and another for the rest.

The principle of equality before the law is the foundation of Australian democracy. Once we start carving out special political rights for one group, we no longer have a government that represents all people equally. Instead of reconciliation, the Treaty risks hardening racial boundaries and perpetuating grievance.

The second problem is accountability. The Treaty process will empower new unelected bodies — such as the First Peoples’ Assembly and Gellung Warl — to influence legislation and government policy.

These organisations will have ongoing consultation rights, budget influence and potentially shared management over public land. Yet the members of these bodies will not be answerable to the broader Victorian public.

Our democracy only works because governments are accountable to voters. Creating race-based institutions outside that framework is a dangerous precedent. Ordinary Victorians will have no voice in how these bodies operate, yet they will pay for them through higher taxes and public debt.

And the cost will be enormous. Even before a single local treaty is signed, the state has already funded offices, commissions, cultural programs and a “Self-Determination Fund” to bankroll negotiations. With Victoria drowning in record debt and struggling to maintain basic services, it’s hard to justify pouring billions more into what is, at best, a symbolic exercise.

Worse still, the Treaty is vague and open-ended. No one can say exactly what it will deliver — whether that means land transfers, co-governance, or even the right to veto government projects.

It will become a perpetual process, with no clear limits on what future governments may be pressured to concede.

Yes, the injustices of the past must be acknowledged. But a treaty signed 200 years after colonisation cannot change history. What it can do is rewrite the present — embedding racial distinction into the laws of a state that should treat all its citizens equally.

Reconciliation should mean coming together, not setting up parallel systems of power. True equality is not achieved through special treatment, but through shared opportunity — better schools, safer communities, and jobs that lift people out of poverty.

Finally, this Treaty lacks public consent. After the overwhelming national rejection of the Voice referendum, it’s clear that most Australians — and most Victorians — do not want a race-based political framework. Yet the Allan Government is forging ahead without a referendum or even meaningful consultation with the broader public.

One people. One law. One future.

Credit: Greg Cheesman