Introduction | The Airport Train in Melbourne has been some time coming.

As many others in Melbourne, a few months ago I was following the progress of the complex negotiations around whether the station at the airport needs to be underground or elevated.

What fascinated me about that discussion was that it was very hard to understand, at least through what I had managed to read on the subject, why the argument (heated enough to require appointing a 3rd party mediator) was at all taking place.

The underground station is obviously a more expensive solution than an elevated one, however, my impression was that the stakeholders advocating for the former were willing to pay extra for whatever the advantages they wanted to pursue, and it was impossible to understand why anyone else would have been unhappy with that idea. Ultimately, the cheaper elevated option was prioritised.

A few weeks later, I got myself scrolling through a Herald Sun newspaper whilst enjoying my morning coffee. Its title screamed (in capital letters): ‘LATE TRAIN PRICE PAIN’. This was referring to the Airport Rail costs growing, and figures like $13bn and even $15bn were mentioned—and the shovels have not yet hit the ground.

Despite both the seemingly high level of support amongst Melburnians and the very real financial commitment from both State and Federal governments, the project seems to be experiencing obvious difficulties when it comes to delivering it.

Could it be that the overall idea is not good as it seems?

As a relatively recent newcomer, and someone who is professionally passionate about trains going brr, I’ve turned myself to the papers outlining the project justification in pursuit of getting to know more about it and how it came to be.

Below is my report on what I have found out, and a few suggestions on what I think needs to happen.

This is an extra-long-read (you have been warned) which comes in the following parts:

- Part 1 | Melbourne does not have an airport train. Is that a problem?

- Part 2 | Even Perth has an Airport Train

- Part 3 | Why Melbourne Airport Rail is the way it is

- Part 4 | Public transport access to/from Tullamarine Airport is not perfect

- Part 5 | The Melbourne Airport Rail Business Case has too many inconsistencies in it

- Part 6 | What I think needs to be done

- Part 7 | How to dramatically improve Tullamarine Airport’s accessibility by public transport, now

- Conclusion

Part 1 | Melbourne does not have an airport train. Is that a problem?

To understand this, let’s address ourselves to the Melbourne Airport Rail Business Case (released in September 2022) which outlines the accessibility problem of Tullamarine Airport in its Chapter 2.

It makes the case for the Tullamarine Airport train connection based on the following premises:

1. The Airport is growing.

Prior to COVID, Melbourne Airport’s patronage has been growing steadily and has increased by 32% between 2011 and 2019. It is expected that after the impacts of COVID-related disruptions wither away, this trend will pick up, and the subsequent growth will have the landside travel demand in Tullamarine airport grow two-fold by 2056.

2. The Airport is overly reliant on car travel.

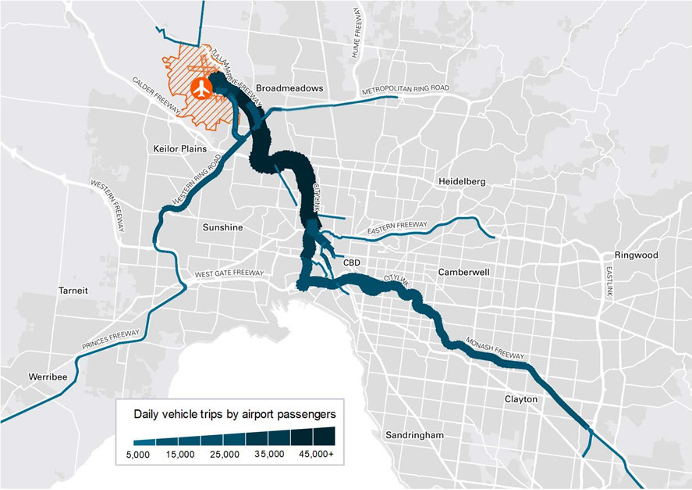

About 90% of passengers and employees travel to the airport by car, including both driving and ride-sharing/taxi.

Most of that travel is cross-city trips, and most of those trips run towards the same areas where one of the busiest railway lines in Melbourne already goes.

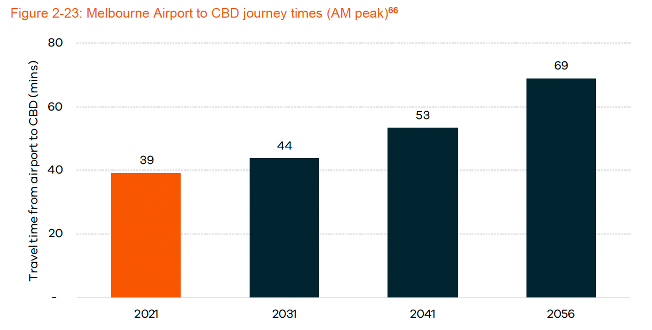

Under the assumption the airport keeps growing as envisaged, the growing travel demand, still reliant on cars, will result in clogging the roadways leading to the Airport and thereby increase the travel times way beyond what’s feasible.

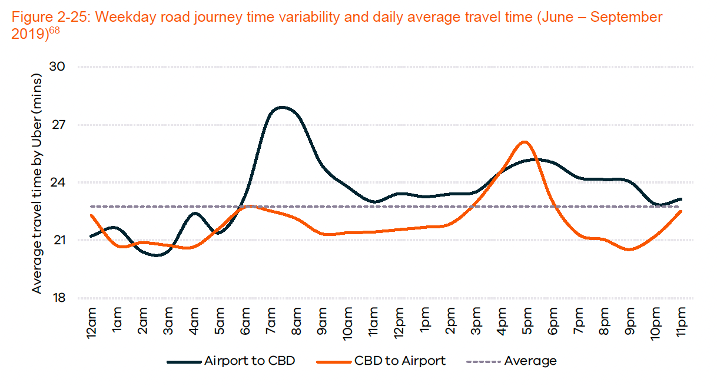

(Note that 2021 travel time is a forecast done through the modelling which took place in 2020. The business case does not seem to make a proper recognition of the rather considerable difference between 27 minutes and 39 minutes. In any case, my perception is that the current travel times to the airport are about the same as they were in 2019.)

3. Tullamarine Airport is among Top-100 high-performance airports, globally. Nearly all of those airports already have a frequent and reliable railway connection.

In a large city with a developed train network—one that already provides frequent services and goes to a lot of places—bringing trains to the airport is often the most efficient way to provide users with abundant regionwide public transport accessibility, and it is therefore a sensible idea to explore in the context of improving airport’s accessibility.

With an abundant railway network in Melbourne already in place, the idea of bringing trains to Tullamarine airport seems like a sensible public transport improvement to pursue.

Part 2 | Even Perth Has An Airport Train

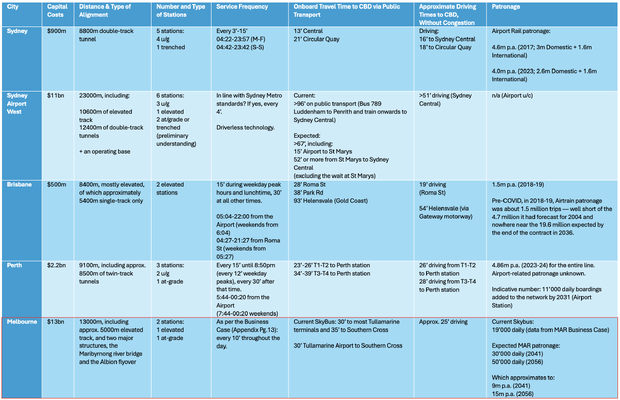

Of all the major cities around Australia, Sydney, Brisbane, and Perth have brought trains to their airports.

All these connections provide direct access to the CBD and primary nodes across the cities’ public transport networks and are therefore useful to travellers.

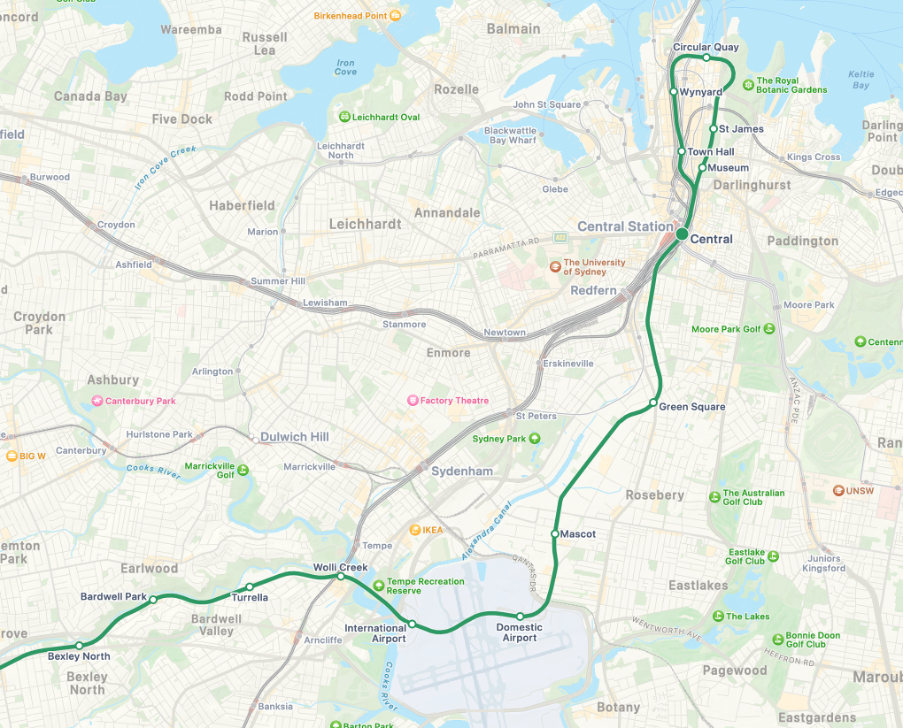

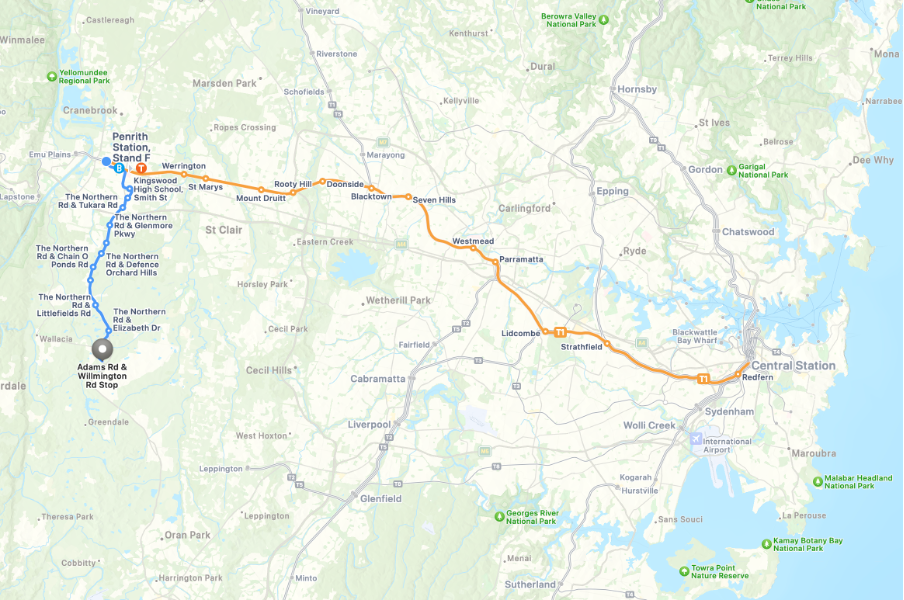

Sydney built their Airport Link in 2000 at the cost of $900m, inclusive of four underground stations (Green Square, Mascot, Domestic, International), as well as the Wolli Creek lower-level platforms (placed in a trench).

Trains pass through Domestic and International on their way to a wide range of destinations (South-Western suburbs to Sydney CBD) and therefore provide very high frequency of service to serve the needs of a much wider customer base than solely the airport users.

The access to all new stations was priced at a premium, however, later on the contractual arrangements around the operations were revised, and Green Square and Mascot stations, which do not serve the airport itself but rather provide access to surrounding suburbs, were spared of the access fee and became treated as regular stations on the Sydney Trains network.

Inadvertently, this has created a shortcut for the Domestic Airport users seeking to save on the airport access fees (currently a little over $17, with the weekly cap of twice as much), as there is a frequent, quick, and easy to use bus link between Mascot and Domestic, which instantly became popular.

Sydney is also building a new airport in its Western outskirts, and a public transport link thereto.

Whilst a direct link from Parramatta (which would very likely be an extension of Sydney Metro West) is strategically envisaged, the first public transport connection, the Airport West Metro line, which is currently under construction, will link it with St Marys station, thereby offering a travel time that is hardly competitive with driving, especially given the distances involved. (This kind of prioritisation is for me extremely hard to understand, however, I’ll leave it for another article.)

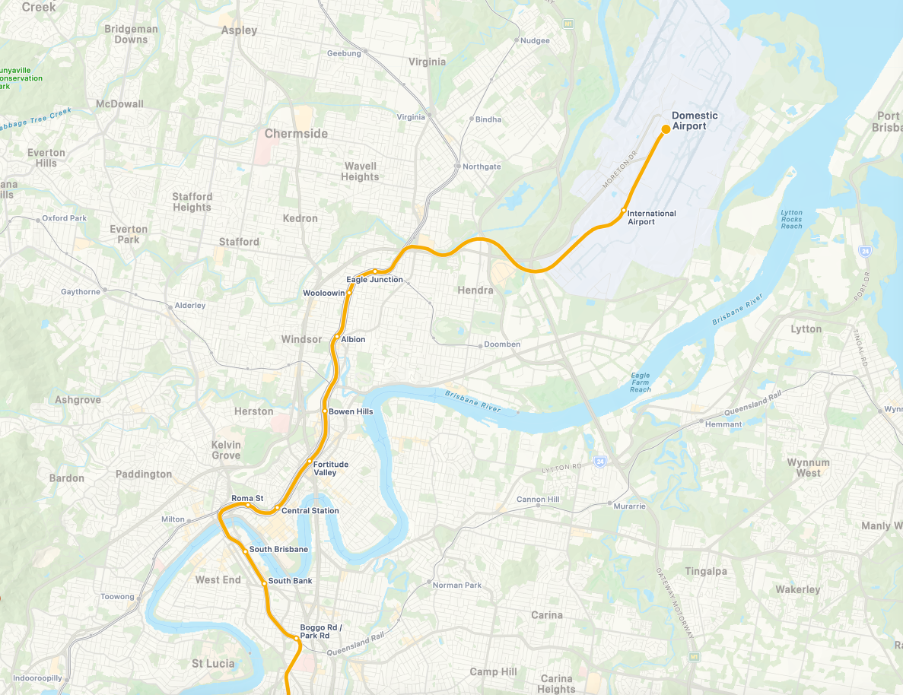

Brisbane built their Airtrain in 2001 at the cost of $500m, inclusive of a simple, mostly single-track elevated rail line and two stations, at International and Domestic terminals. The line branches off Eagle Junction station and is a stub end with no real possibility for being extended anywhere North of the Airport.

Some Airport services run beyond Brisbane, all the way to Gold Coast.

With the initial decisions around the chosen delivery model, Brisbane ended up having done everything to make the public transport access to their airport as painful as it can be—despite all the investment.

The frequency (30 minutes at most times – more than the onboard travel time to the CBD!), span (trains available till 10pm only), and pricing (nearly $22 per trip) of the AirTrain services have been off-putting, and any other means of public transport access to the airport were intentionally not provided.

Twenty-three years later, however, this is becoming addressed.

Alongside the infamous 50-cent public transport fares campaign in Queensland, a 50% discount has been introduced on the AirTrain service, thereby bringing the single-trip fare down to the much more reasonable $10.50. This was also followed by the recent announcement of the intent to extend Brisbane Metro (bus rapid transit) to the airport by 2032, which means the exclusivity of the AirTrain as a public transport means of access to the airport will be over.

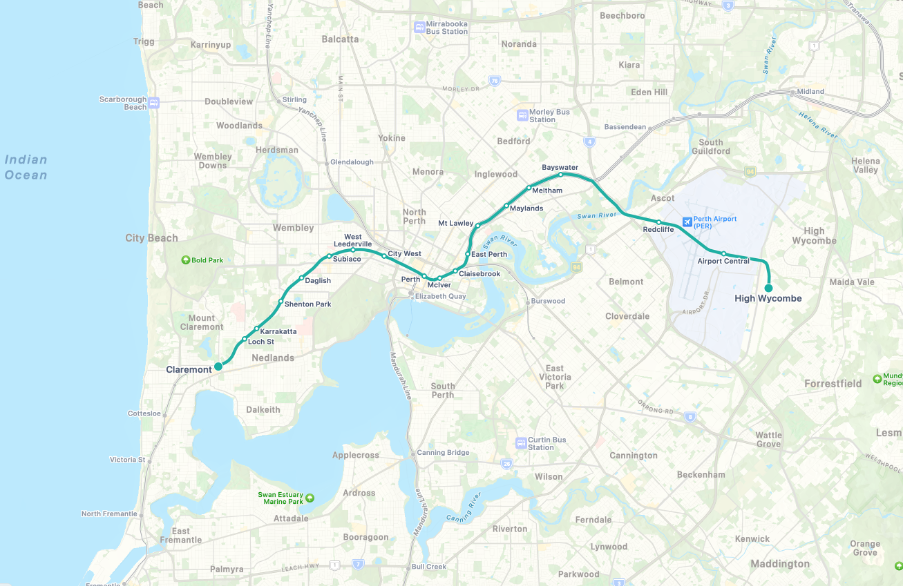

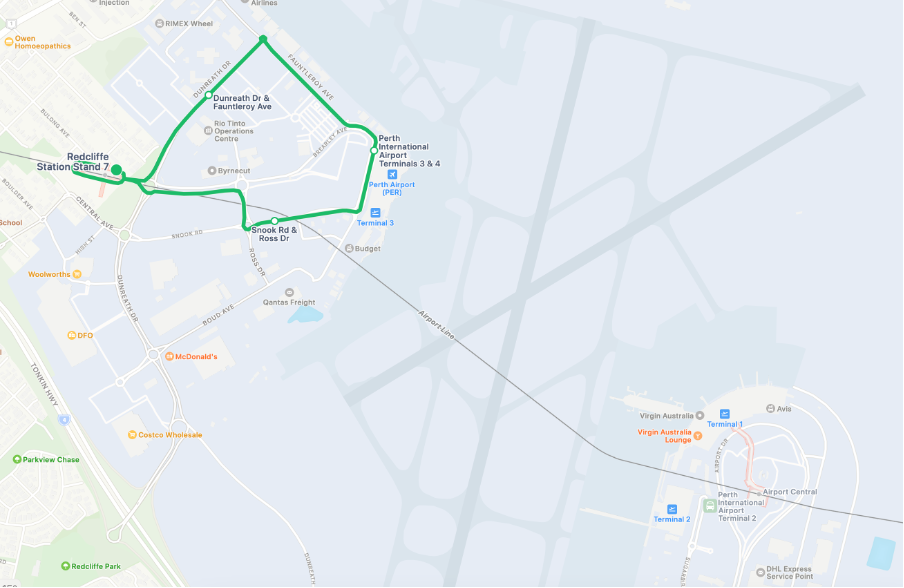

Perth added itself to the list in 2022, having built Forrestfield – Airport railway line at the cost of $2.2bn, inclusive of two underground stations (Redcliffe, Airport Central) and a High Wycombe station which is at-grade.

Airport Central station is located right next to the T1-T2.

Redcliffe station, however, is nearly a kilometre away from T3-T4, and is presently connected to the terminals with a shuttle 292 bus route.

In 2025, as part of the Perth Airport Master Plan, the new Consolidated airport terminal will be delivered in its entirety (the current T1-T2 being its already operational half), and the existing T3-T4 will be discontinued and demolished, with further re-development of their site as a dense office and residential precinct. Redcliffe station will therefore become central to the area and no more related to the airport operations.

There are no premium station access fees in Perth: both airport stations are accessible with a regular public transport fare, which is presently no higher than $5.20 for a single trip (two or more zones).

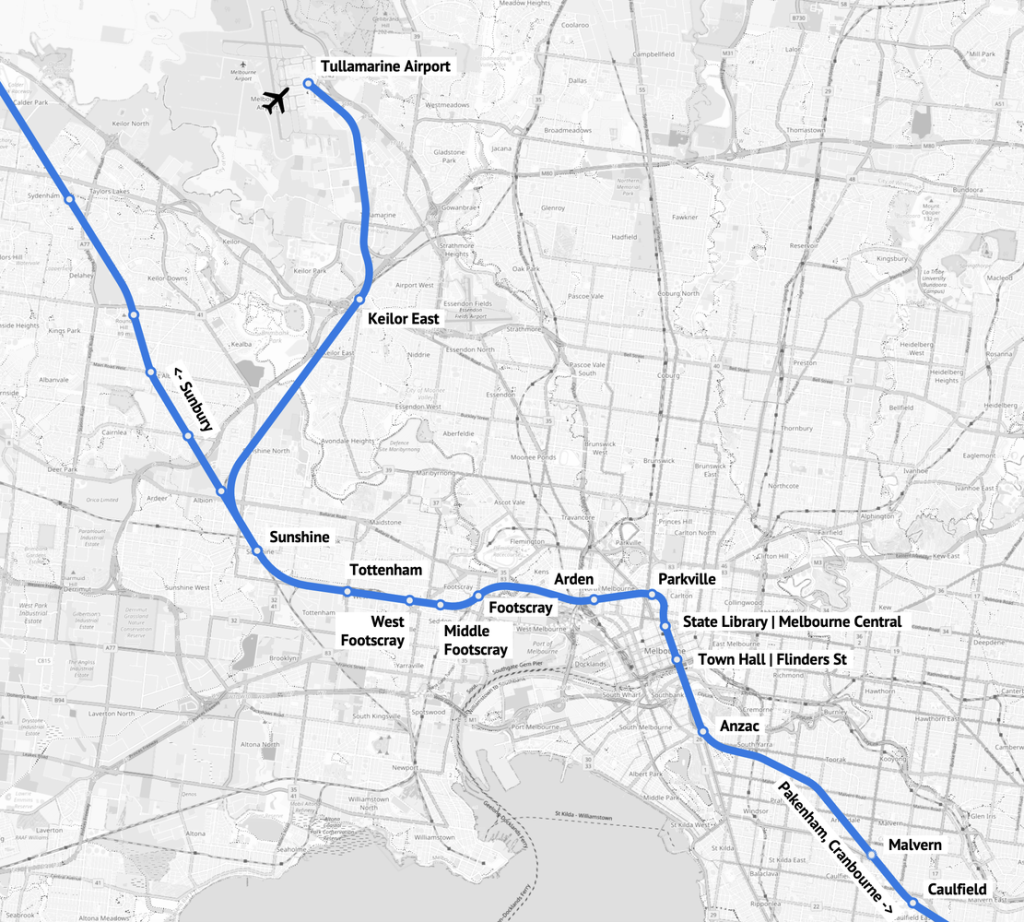

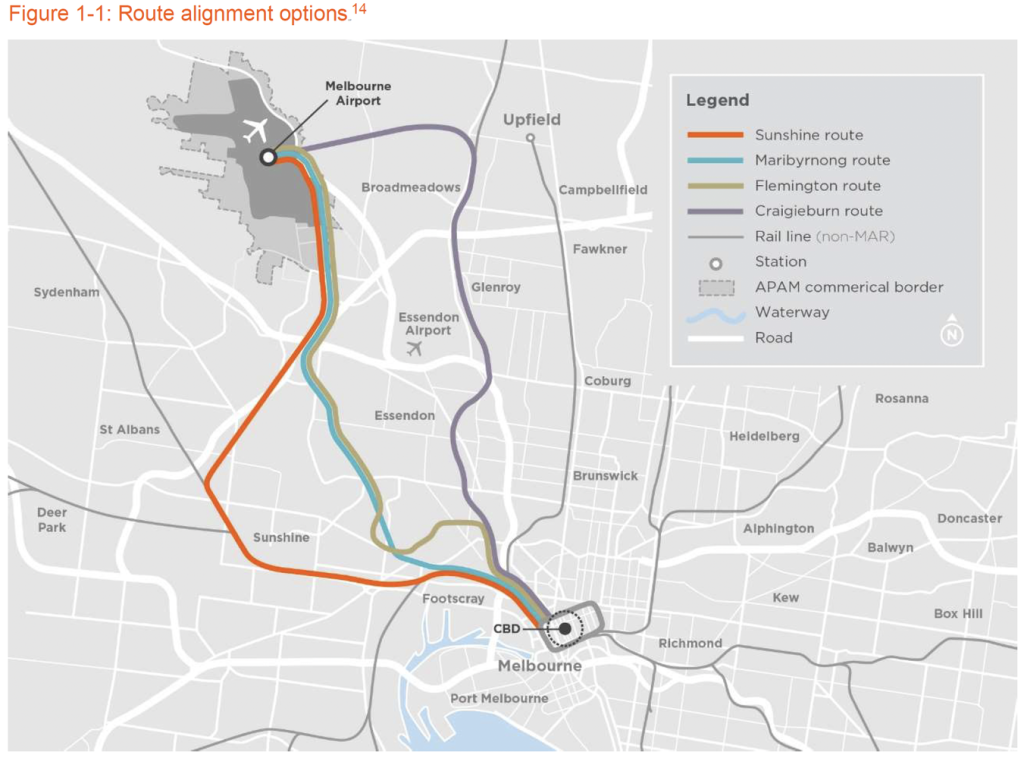

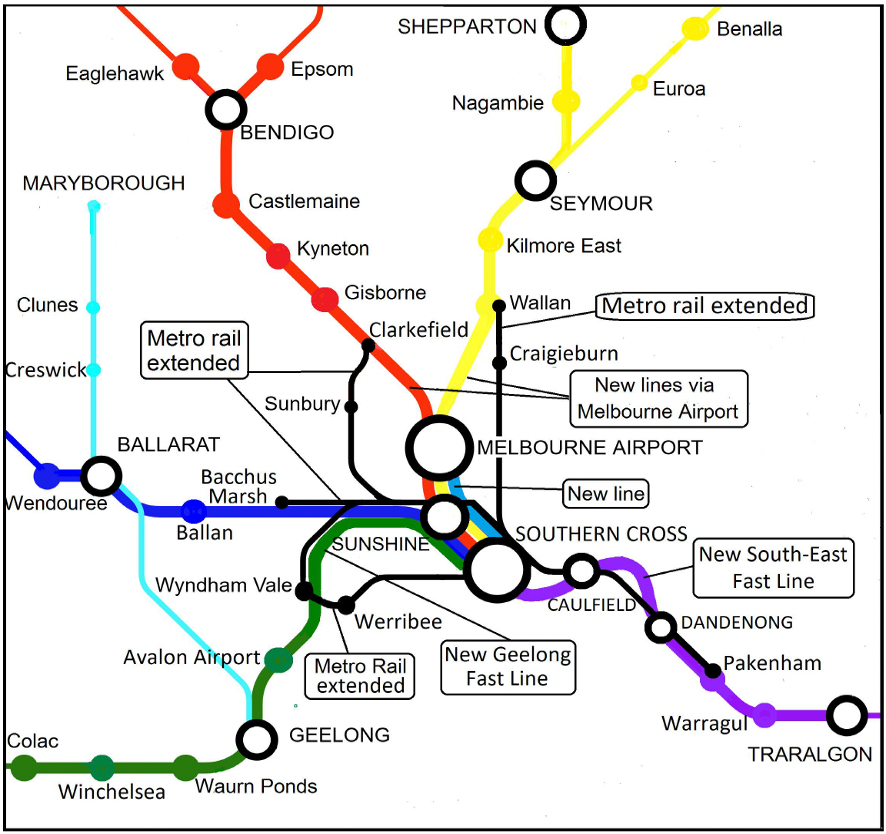

The Melbourne Airport Rail Line will take advantage of the available railway corridors between Melbourne CBD and Sunshine (Albion), then proceeding alongside an existing broad-gauge Albion-Jacana freight line to a new Keilor East station, from where it would leave the existing right-of-way and proceed to the Airport on an elevated structure along Airport Drive.

Airport Trains will be through-running with Cranbourne and Pakenham lines via the Metro Tunnel stopping at Town Hall (Flinders St), State Library (Melbourne Central), Parkville, Arden, Footscray, West Footscray, Middle Footscray, Tottenham, Sunshine, Keilor East, and Melbourne Airport.

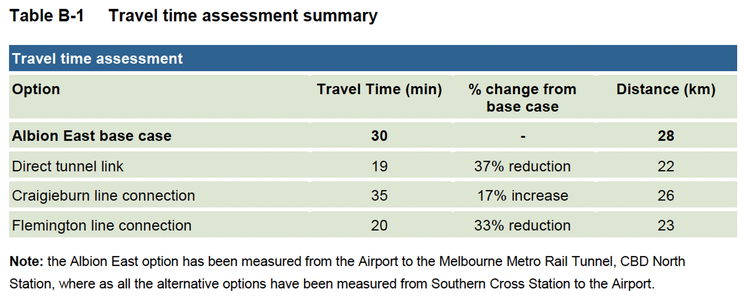

Once placed into the comparison summarised below, Melbourne Airport Rail project is visibly different from its peers by a range of parameters.

The onboard travel time between CBD and the airport is stated as 30 minutes, which is a limited improvement over SkyBus which makes the way to the airport in about the same amount of time (even though the way back is a bit longer), and the frequency of service—every 10 minutes—will remain the same as currently provided by SkyBus.

The expected patronage of the project, however, is more than two to three times the current busiest airport’s rail link patronage (Sydney).

But most importantly, the cost of the project is estimated at around $10bn – with some media publications already suggesting it is by now pushing the boundary of $13bn.

$10bn is five times the cost of the most recent project of a comparable scale (Perth) or, adjusted over the 23 years, nearly four times the cost of the largest project of this kind (Sydney).

The entire Melbourne Metro Tunnel, which has 5 underground stations of utmost engineering complexity in it, costs around $13.5bn (after the most recent adjustment of $0.84bn).

I have questions.

Why is Melbourne Airport Rail so expensive?

Why is this a line so indirect?

And what can and should be done about it?

In pursuit of trying to answer any of those, let’s explore how the current proposal for the Airport Line was shaped and try to follow the logic behind it.

Part 3 | Why Melbourne Airport Rail line is the way it is

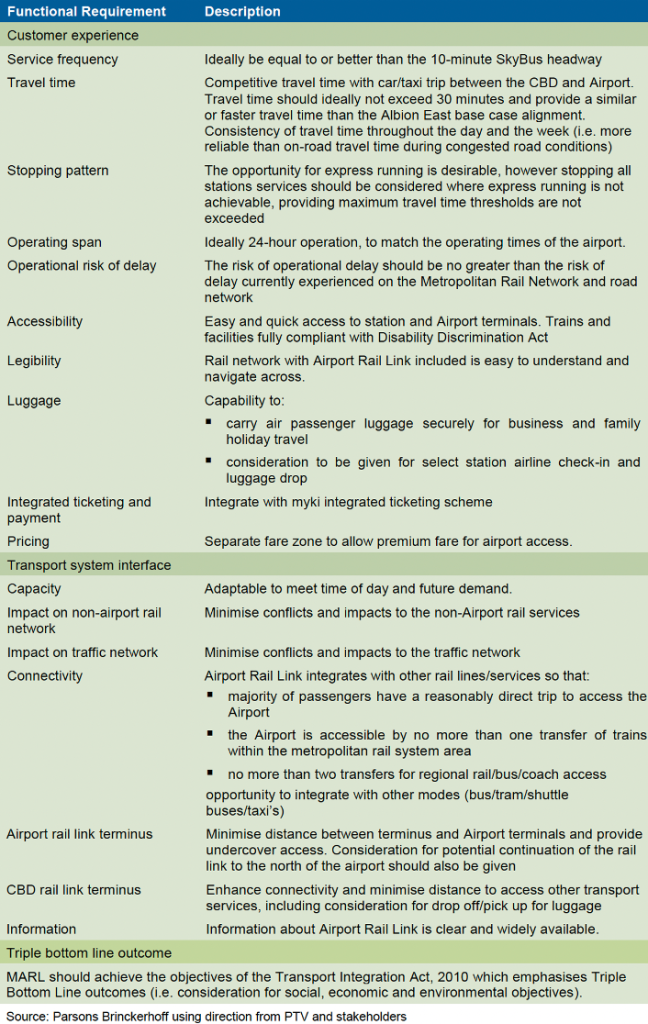

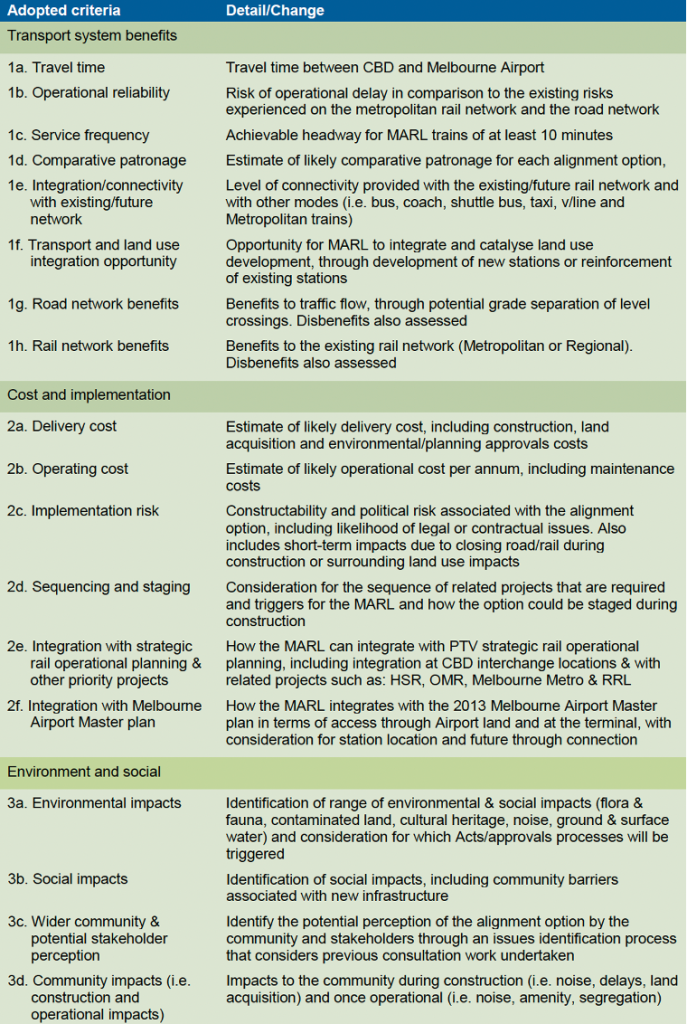

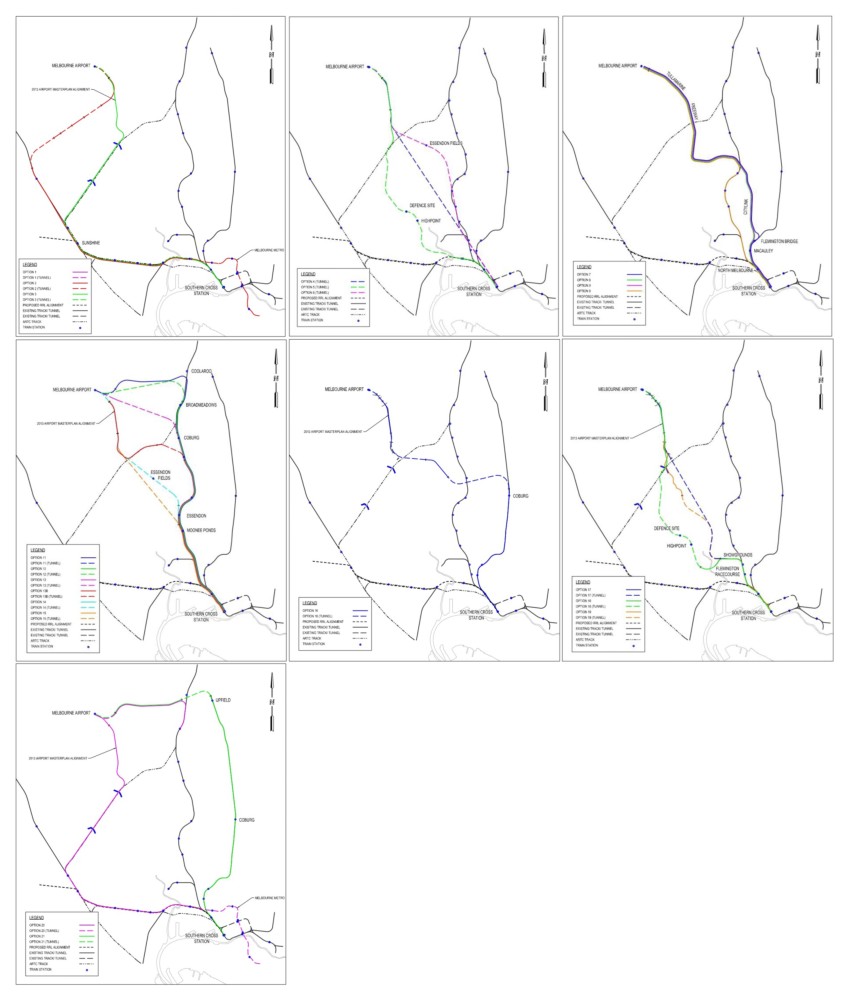

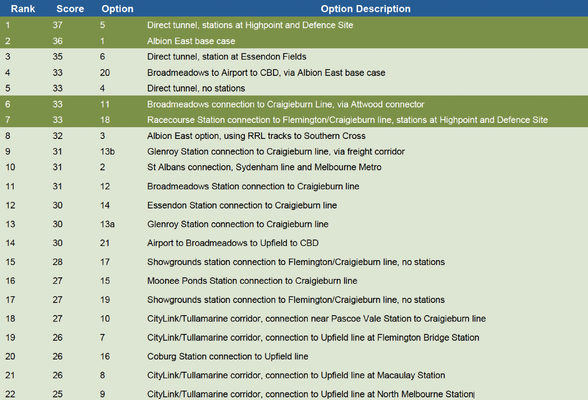

In 2012, pursuing to move the project forward, Public Transport Victoria commissioned the Melbourne Airport Link Alignment Alternatives Study.

This work sets the main functional design requirements for Melbourne Airport Rail and translates them into a system of evaluation criteria through which 21 different options of bringing the rail into the airport are considered.

A multi-criteria analysis approach was used to short-list four options out of the initial 21.

It considered 17 different criteria which were all classified more broadly in three groups: Transport System Benefits, Cost and Implementation, and Environmental and Social.

Each of the options has therefore received 17 marks (at the spectrum of 0 to 3, where 3.0 is the best performing – it should be noted, however, that the exact equations behind the assessment of each of those components are not provided) which were subsequently summed up to get the resulting rating for each option.

A useful public transport service is the one that is designed to be so: it is there whenever people might need it, it goes where they need to go, and it does so in a predictable and reasonably direct fashion.

The most direct way of connecting two dots on a plain is a straight line.

This essentially sets the scope for a sensible Airport Rail Service: it has to be frequent, available at all times, connected well with places and other services, reliable, and fast.

For a project that seeks connecting the airport and the CBD in a reasonably direct fashion, the set of options short-listed as the result of the MCA (rated 1st, 2nd, 6th, and 7th, respectively) looks like a somewhat unusual choice.

The four chosen options were Sunshine, Maribyrnong, Flemington, and Craigieburn (Broadmeadows) routes.

The most geometrically direct option would have been a branch from Essendon station.

It did not make it through the MCA[1]: somehow, among all the Craigieburn routeoptions, it ranked the poorest, whereas the preferred option—all stations via Broadmeadows—was chosen despite clearly not meeting the 30-minute travel time threshold.

The latter, as per the functional requirements for the project, should have been the reason enough to throw the Broadmeadows option away.

The Maribyrnong route (with two interim stations, at Highpoint and Defense Site) ranked the highest among all 21 options and is deemed to provide a 19-minute[2] one-way travel time between the CBD and the Airport.

The Sunshine route option (‘Albion base case corridor’) came second in the overall MCA (scoring 36 points), with high transport benefits and, more importantly, considerable advantages in terms of the overall cost compared to any other option.

The Flemington route option was shortlisted as a ‘cheaper’ sub-option of Maribyrnong route (which scored well), even though, for some reason, it scored perceptibly more poorly.

Options 6 and 4 were excluded from the assessment, as they were deemed not sufficiently dissimilar from Option 5 which scored at the top, and Option 20 was requested to be excluded because, among other reasons, it ‘effectively requires the construction of two airport links…’ instead of one[3].

[1] Option 14 scored 30 points. Option 6, involving tunnelling all the way from Southern Cross to the Airport with the only interim station at Essendon Fields, scored 35 points, with better performance across all groups of criteria, and was the second preferred after the Option 5 via Maribyrnong Defense Site (37 points) of all the Direct Link options.

[2] The notes in the report at first mention 13 minutes, however, further down the document this is adjusted to 19 minutes, which seems a much more reasonable estimation.

[3] In 2012 no-one knew Suburban Rail Loop would become a thing, and ‘construction of two links instead of one’ is what the actual current plan is.

How do the options that seem to be so compromising upon the primary reason for the project to exist end up on a short-list of such a process? These kinds of issues lie in the methodology.

In the Rapid Appraisal multi-criteria analysis, the travel time between the Airport and the CBD, which is of paramount importance to the overall success, was considered as one of the 17 terms in the total sum. This has opened a possibility for flawed outcomes: an option that would make no sense in terms of travel time but score excellently on all or most other aspects could still make it to the top.

For example, the ‘Comparative Patronage’ metric within the ‘Transport System Benefits’ group of indicators was treated as ‘Measure of Population and Employment data (2031) within 3km of stations, considerations of secondary factors, including connectivity, frequency, and land use uplift potential’, or, basically, Future Catchment.

Catchment on public transport is tricky, as it depends on where the line goes and how many stations (with people and places around them) are on the way.

Treating catchment without considering either of these aspects may result in assessments that favour considerably slower (through the denser stop spacing) and/or less linear routes (through the deviations towards other destinations) over more direct ones, even though what matters for the overall patronage (let alone the key audience of a service which purpose is claimed to be to connect the Airport and the CBD) is that the service is reasonably direct and fast.

That seems to be the case here: Broadmeadows route has more stations on the way than any other station. Naturally, it would have a higher Future Catchment than anything else. But this comes at the massive cost of travel time impacts.

We can trace this problem back to the detailed scoring table which the 2012 report generously provides. There, we can see that Craigieburn sub-options all rank on this component in the near-opposite fashion to their expected travel time (Option 11 Coolaroo being the longest route with the rating of 2.8, and Option 15 Moonee Ponds being the most direct route with the rating of 2.1).

In the remarks to Option 11 being short-listed, the authors make a direct reference to the ‘strong population and employment capture, stopping at 13 stations on route to the Airport, including the Broadmeadows activity centre.’

Serving all those stations by the Airport train would not serve that pattern much better but would come at a cost of increasing the travel time between the CBD and the Airport up to 35 minutes—thereby affecting everybody else.

Moreover, many people living in Broadmeadows and in the vicinity of other Craigieburn line… already take Craigieburn line and change for 902 bus at Broadmeadows to get to the Airport, hence the benefits of providing the airport trains to them would have been nowhere near as impressive as the authors might have assumed.

Modern techniques of accessibility analysis express the benefits, costs, and how they change against the decisions around various trade-offs as one above, much better than a table-based multi-criteria approach can possibly do.

Unfortunately, that kind of analysis has only been provided four years later for the selected preferred option alone. Stay with me, dear reader, and I’ll get to exploring its outcomes in a bit.

Why did the Sunshine route become the preferred one?

All these complications notwithstanding, Sunshine route came 2nd in the multi-criteria assessment, whereas Maribyrnong route (via Highpoint and Maribyrnong Defence Site) came 1st.

The reasons for moving forward with the Sunshine route anyway are rather modestly outlined in the 2018 Sunshine route Strategic Appraisal.

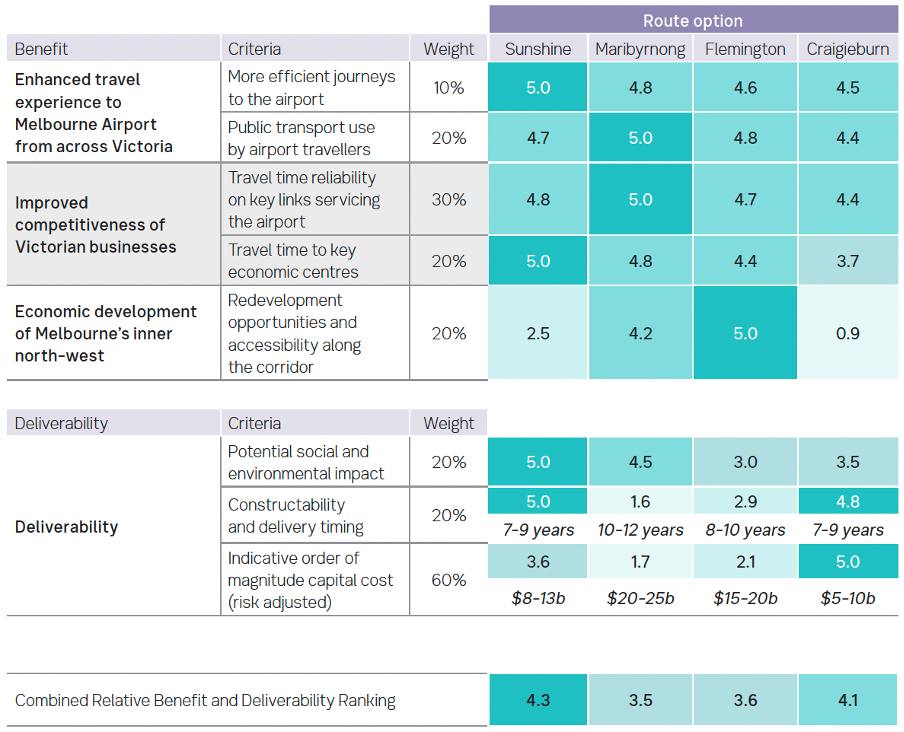

It takes the four pre-selected options and rates them against a set of weighted criteria, including aspects of wider benefits and project deliverability.

As the ranking methodology is not provided, it is not possible to track what exactly went into each of the scores, what these numbers actually mean, or what the rationale was behind the criteria weights applied. (It is also hard to understand this kind of approach to public reporting.)

It can be ascertained, however, that the greatest importance is now placed on travel time benefits against capital costs, whereas other aspects involved are treated as less important. And, again, here we can see the multi-criteria approach not prone from flaws: even though the Craigieburn route option is known to not meet the threshold of 30 minutes of travel time set in the previous study, in this assessment it somehow rates rather not too poorly on the benefit side, and with its capital costs being the lowest it almost ends up being the leader.

The latter of itself presents a methodological issue.

On public transportation, unlike with roads, it is not merely sufficient to build the new structures so as to realise the benefits of its delivery; service must be operated, i.e., in this instance, the trains need to run.

The service delivery aspect is indelibly linked with both the benefits and the costs, and with the extremely long infrastructure lifecycles involved, the total service costs accumulated over the same timeframe would be a very significant amount of the total project lifecycle costs.

Maribyrnong option is both considerably faster and shorter, thereby requires fewer train-km and train-hrs to operate the same service level, in terms of frequency and span, than any other option considered. This represents a substantial amount of savings on the OPEX side of the equation, even though the CAPEX of a tunnelled route is higher.

The decision-making based on the CAPEX alone does not have me fully convinced.

The 2018 Strategic Appraisal furtherly comments the choice to pursue Sunshine route by pointing out three main reasons for doing so.

1. It says, compared to Maribyrnong and Flemington options, the ‘travel times to other employment clusters and middle and outer metropolitan suburbs were better as airport services can more efficiently connect to Melbourne’s south-east and a higher number of other lines’.

I find this difficult to understand, as these three options can all connect to the Metro Tunnel in exactly the same fashion, and therefore travel time benefits should be related to how direct and fast the connection between the Metro Tunnel ramp in South Kensington and the Tullamarine Airport station would be.

2. Duly reflected further on, the only meaningful difference the airport trains going through Sunshine station deliver in terms of the overall network connectivity is that it enhances connections with Bendigo/Ballarat/Geelong regional lines which all pass through Sunshine on the way to/from the city.

We must generally agree with the logic here: the need for taking the SkyBus to Southern Cross to jump on a V/Line to any of those destinations indeed wastes a lot of users’ time, especially when compared with driving. Providing superior connections to regional Victoria at Sunshine is indeed a strong accessibility argument. But why do we need specifically the citybound airport train making that link? It is not obvious, at all.

3. Finally, it points out the argument that the use of the existing rail corridors (which are present along almost the entirety of Sunshine route, except for the stretch along Airport Drive that doesn’t yet exist) may expedite the project delivery and help to save costs.

This may be a reasonable strategy. Not only using the existing right-of-way is known to be able to save the costs (such as on land, ground works, utilities, and so on, all of which taken together may easily be a substantial amount of money and time!). It may also be the least disruptive to the residents, as new trains will be running where many others already are, and the main construction sites would barely affect any residential areas.

However, we now know as a matter of fact that after the production of this assessment Perth has conceived, designed, built, and begun operating the Forrestfield—Airport Link rail line which not only involved extensive tunnelling and construction of two underground stations, but also cost $2.2bn, with the delivery completed in 2022.

With that in mind, I find it extremely hard to understand how Melbourne Airport Link, in its most affordable bracket (Broadmeadows route notwithstanding) ended up costing nearly four times as much in terms of CAPEX.

Neither the 2012, nor the 2018 study reports mention any form of benchmarking of similar projects taking place (neither Australian, nor international), and the answers to that concern are yet to be found.

The Business Case released in 2022 provides the following information regarding the costs of Melbourne Airport Rail delivery:

…yep.

How useful is Sunshine route?

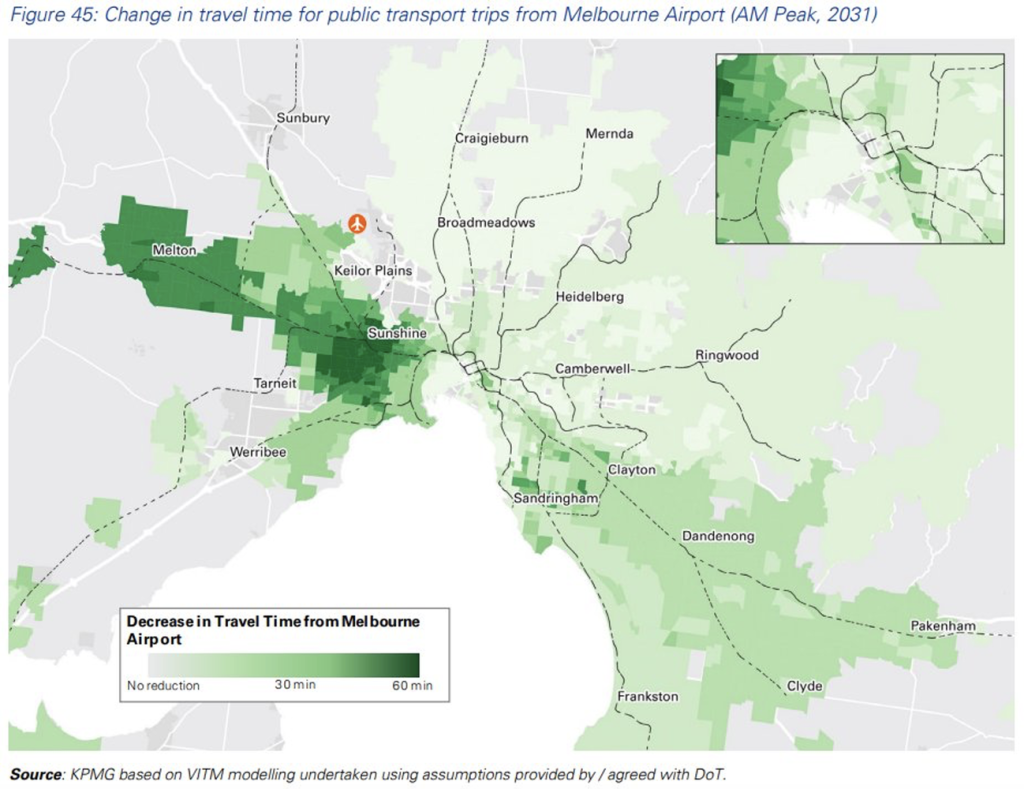

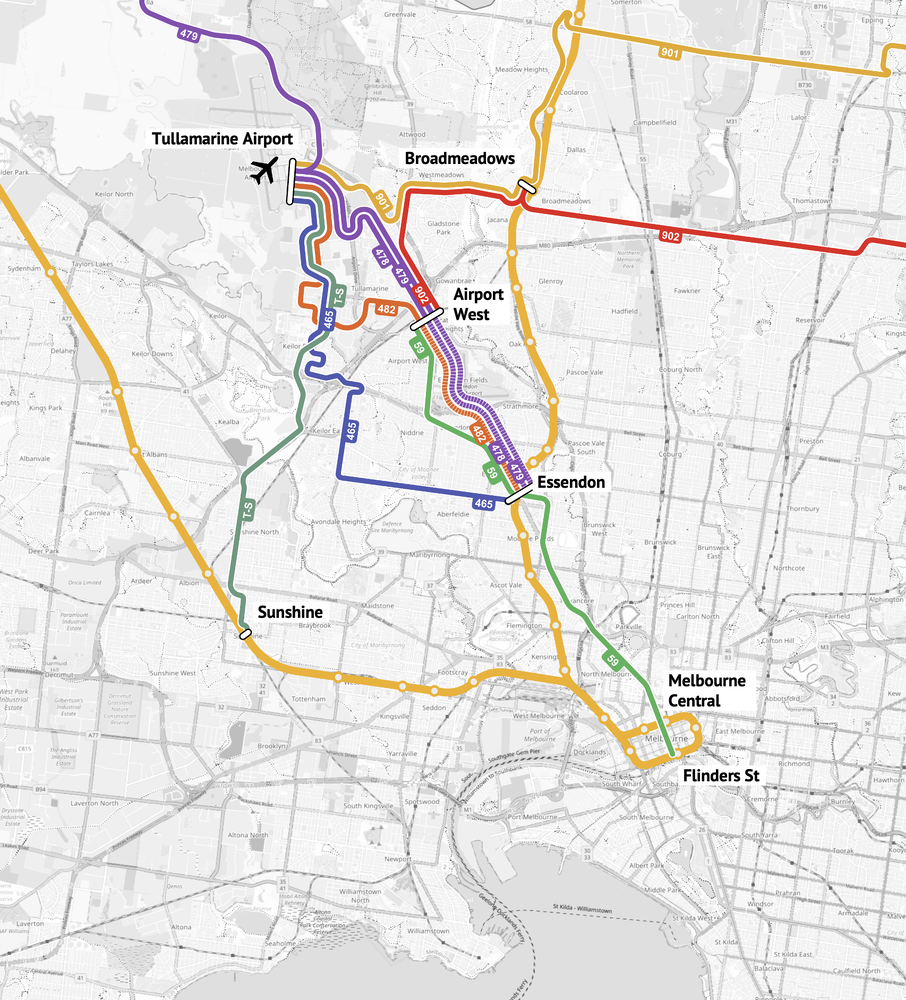

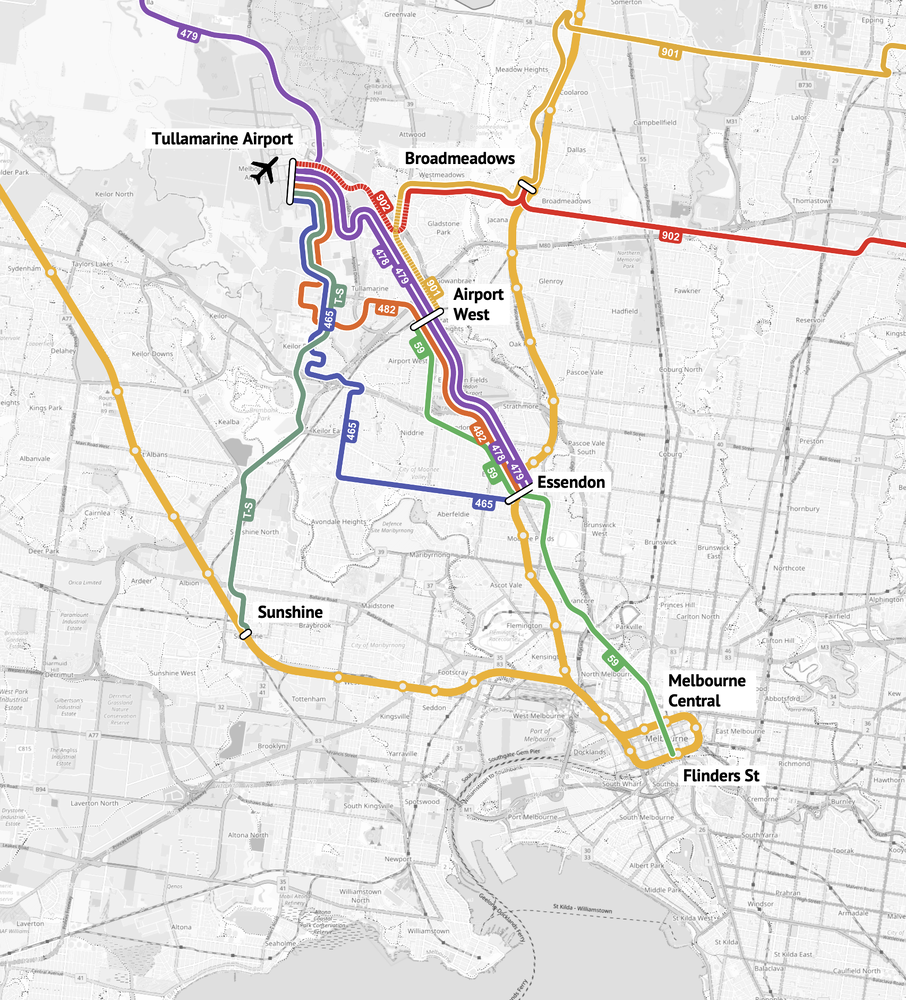

The 2022 Melbourne Airport Rail Business Case elaborates on the chosen route (Sunshine) and, among other things, presents to us the map that illustrates the Airport travel time decreases (or, to put it in another way, the regionwide Airport accessibility improvements) estimated for areas across Greater Melbourne. (No similar analysis for any other option is provided.)

As we already know, most of the Airport’s users currently travel to the CBD and further to the South East along Monash highway. Logically, the Airport Rail project establishes a continuous train service between the Airport and the South East by through-running to Pakenham/Cranbourne lines.

With the Airport-to-CBD travel time of 30 minutes being highly comparable to what SkyBus does now, the primary gain for everyone in the South East is therefore the eliminated need to change between Pakenham/Cranbourne trains and SkyBus at Southern Cross. That eliminates the walk and the wait that occur within that frame, which in total may take, on average, about 7…8 minutes.

It is exactly this gain that we can see in the accessibility map above, around the South East.

But what draws my attention more than anything else are the Airport accessibility gains in Sunshine and its immediate surroundings. They are almost too good to be true: the new project cuts the travel times by nearly 60 minutes.

Why would they be that impressive?

To understand this, let’s have a look into what public transportation around Tullamarine Airport does today.

Part 4 | Public Transport Access to/from Tullamarine Airport is Not Perfect

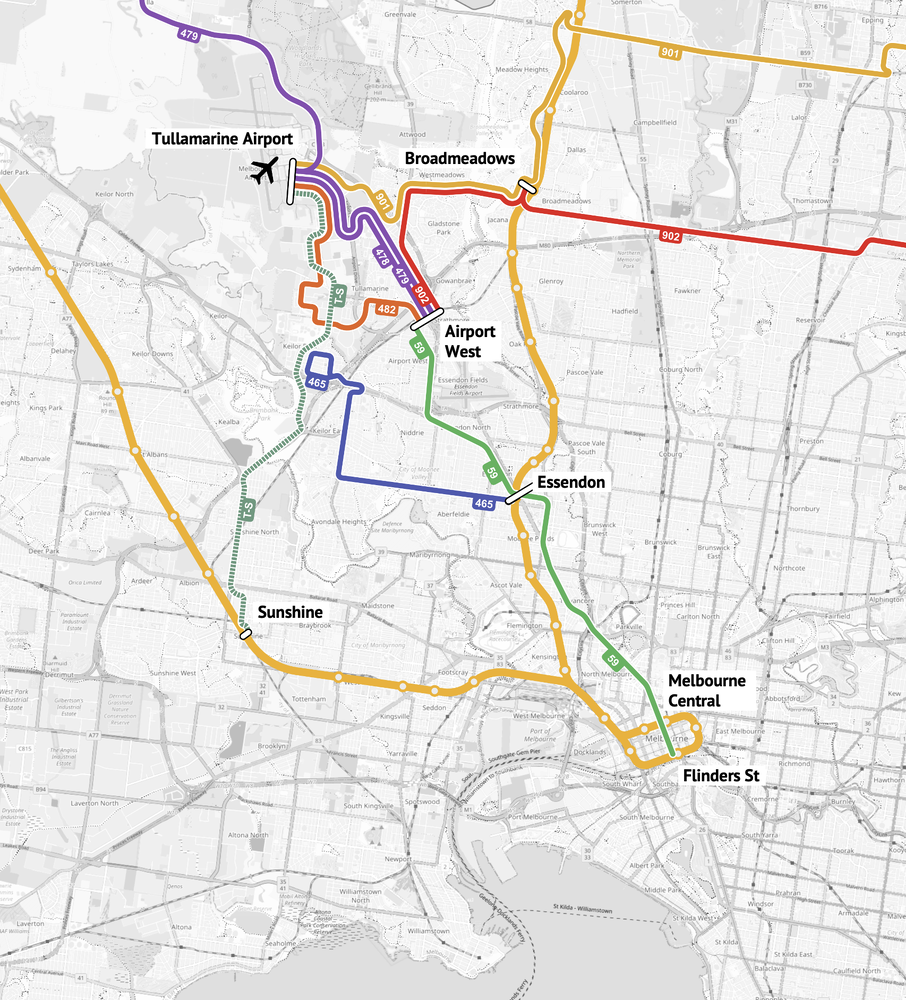

There are two ways of getting to and from Tullamarine Airport: premium-fare Airport express buses and regular-fare public transport (city buses, including in conjunction with other buses, trams, and trains).

1. Airport express buses

Melbourne Airport’s primary public transport connection today is SkyBus, an airport express bus service.

Before COVID, SkyBus used to operate a wide network consisting of four services to the city (City Express to Southern Cross, Peninsula Express to Frankston, and routes to Southbank via Docklands and St.Kilda) and two suburban services via Metropolitan Ring Road (Eastern to Ringwood and Western to Werribee).

Presently, only City Express and Peninsula Express SkyBus services are operational.

City Express runs every 10 minutes between Tullamarine Airport and Southern Cross and is served by double-decker buses with up to 72 people of seated capacity.

In the airport, it follows a one-way circulation stopping at T2-T3-T4 first and then at T1 (Quantas), therefore for most people it takes about 30 minutes to get to the airport, and around 35 minutes to get back to the city.

Peninsula Express is a supplementary service for the South-Eastern suburbs.

It largely follows Frankston line and only runs 14 times on a weekday and 9 times a day on weekends. It is served by single-deck buses which can take up to 42 people on board.

Regional airport express bus services are currently provided by private operators and go to Geelong (hourly), Bendigo (bihourly), and Ballarat (approx. bihourly).

All these services (SkyBus and others) are not integrated with the regionwide Myki fares and are available at a premium fare of over twice the daily Myki fare cap. SkyBus, however, is available for airport workers at a highly discounted rate (approx. $200 for 40 trips).

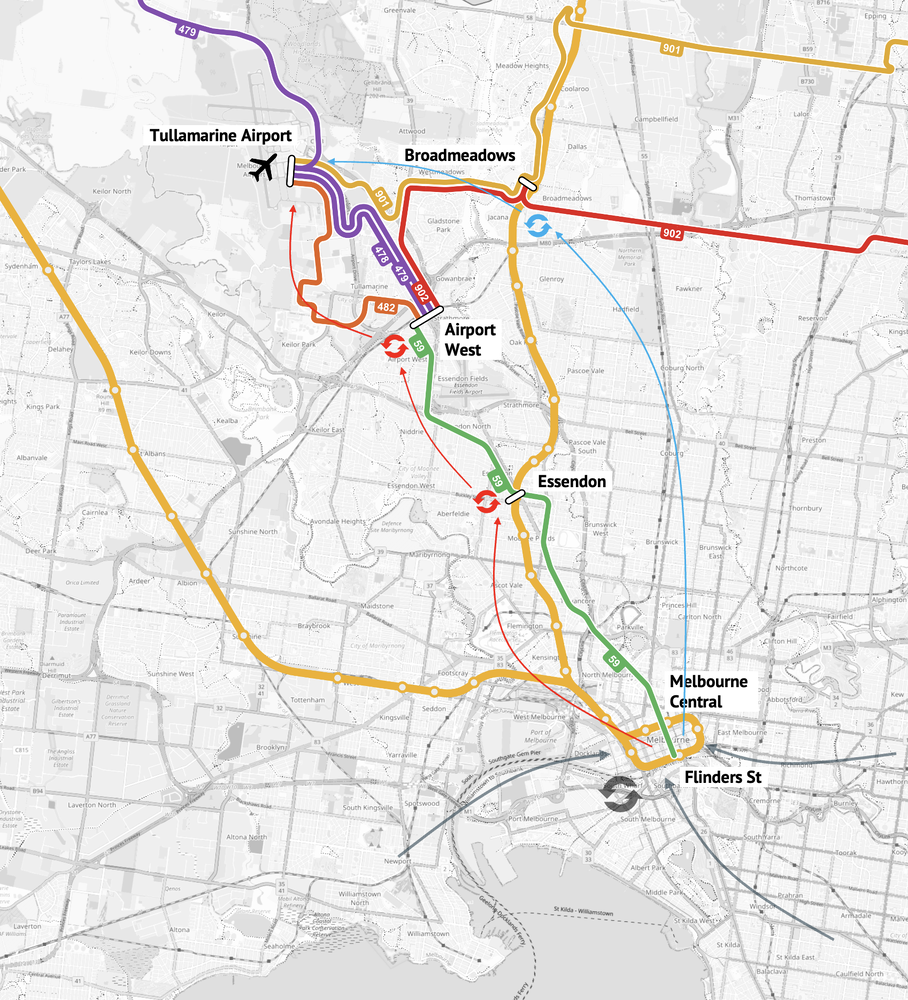

2. City Public Transport

There are two options of getting to and from Tullamarine airport with City Public Transport:

– via Broadmeadows (Bus 901 and Craigieburn train) and

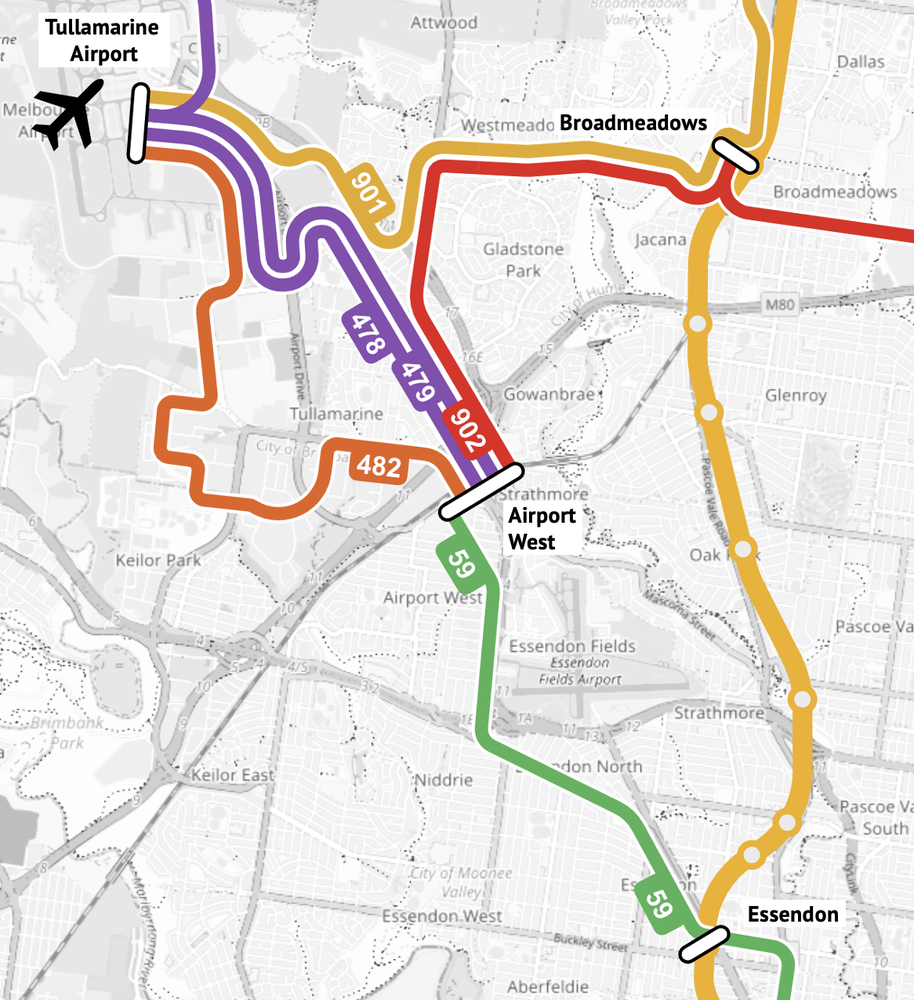

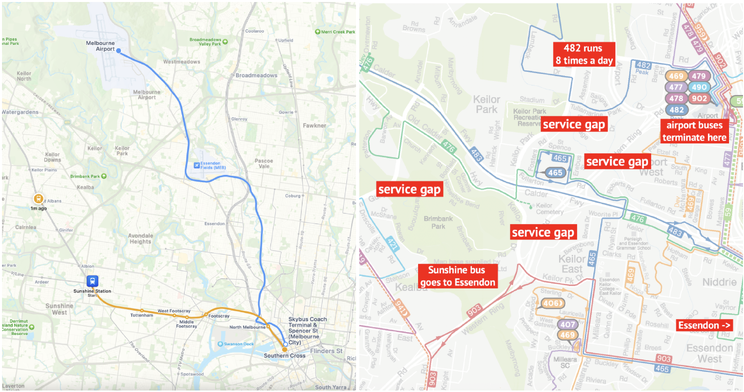

– via Airport West (Buses 478, 479, 482 and Tram 59).

Via Broadmeadows:

Broadmeadows is a major station on Craigieburn line which also hosts V/Line services to Seymour, Albury, and Shepparton, and the intercity trains to Sydney.

Route 901 runs every 15 minutes on weekdays (till midnight) and every 30 minutes on weekends (till 9pm).

It connects the airport with the nearest train station and proceeds onwards through Outer North and East suburbs (Roxburgh Park, Epping, South Morang, Greensborough, Blackburn, Ringwood, Dandenong, Frankston).

The frequency of 901 bus at times does not match with the lower frequency of train services at Broadmeadows (20 minutes during interpeak), which means random and sometimes severe waits are involved when changing between the two.

Via Airport West:

Located nowhere near Tullamarine airport, ‘Airport West’ is the current terminal of Tram 59 which runs from there to Flinders Street station via Essendon, Mount Alexander Rd, Flemington Rd and Elizabeth St.

Three bus routes connect ‘Airport West’ with Tullamarine Airport: 478, 479, and 482.

Routes 478 and 479 offer a combined frequency of 2 per hour on weekdays and 1 per hour on weekends (every second bus runs as route 479 past the Airport to/from Sunbury)

Route 482 only runs during weekday peak hours, with four trips in the morning and four in the afternoon.

While Tram 59 provides very frequent service, it is not always possible to predict which one should be taken from the city to Airport West to connect smoothly to one of the buses above. A minor delay on the way from the city may therefore result in missed connection at Airport West, with the next bus coming in another half an hour, at best.

With all these complexities and uncertainties involved, a one-way trip to the airport by public transport (except SkyBus) from the inner city exceeds an hour one-way and is extremely unpredictable.

…And here comes the answer to our question.

The year 2031 travel time benefit analysis for the Melbourne Airport Rail shows, by far, the highest accessibility benefits of the project for Sunshine (around 60 minutes). This may create an impression that the entire Melbourne Airport Rail project is indeed the very tool to deliver these accessibility benefits.

However, the fact is: there simply isn’t any public transport service running between Sunshine and the Airport right now. It is impossible to make such a trip in a reasonable manner by public transportation.

The assumptions behind the Melbourne Airport Rail accessibility benefit analysis simply treat the absence of buses between Tullamarine and Sunshine as an unchallenged input for year 2031.

This doesn’t make any sense.

Part 5 | The Melbourne Airport Rail Business Case has too many inconsistencies in it.

It claims the travel time to the airport on SkyBus will grow more than two-fold.

Bus lanes are a known recipe to ensure travel time reliability. None of the studies into the airport rail link seem to have considered the introduction of those; this was not part of the scope.

But what happens to this part of the justification of Melbourne Airport link project… if the bus lanes are provided? Wouldn’t this two-fold travel time increase, under this very basic assumption, simply fail to materialise?

Moreover, given the fact the delivery of a rail line project would—under favourable circumstances—take nearly a decade (from the day the shovels hit the ground), the introduction of bus lanes may need to happen if the traffic situation gets to significantly affect the service reliability of SkyBus before the trains reach the airport.

This important part of the storytelling is missing.

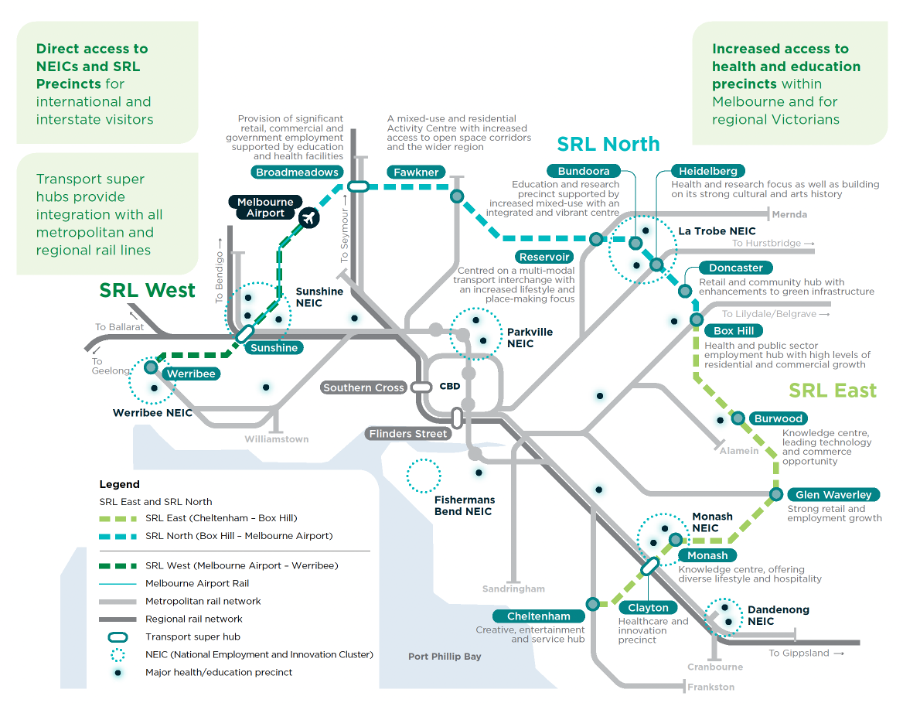

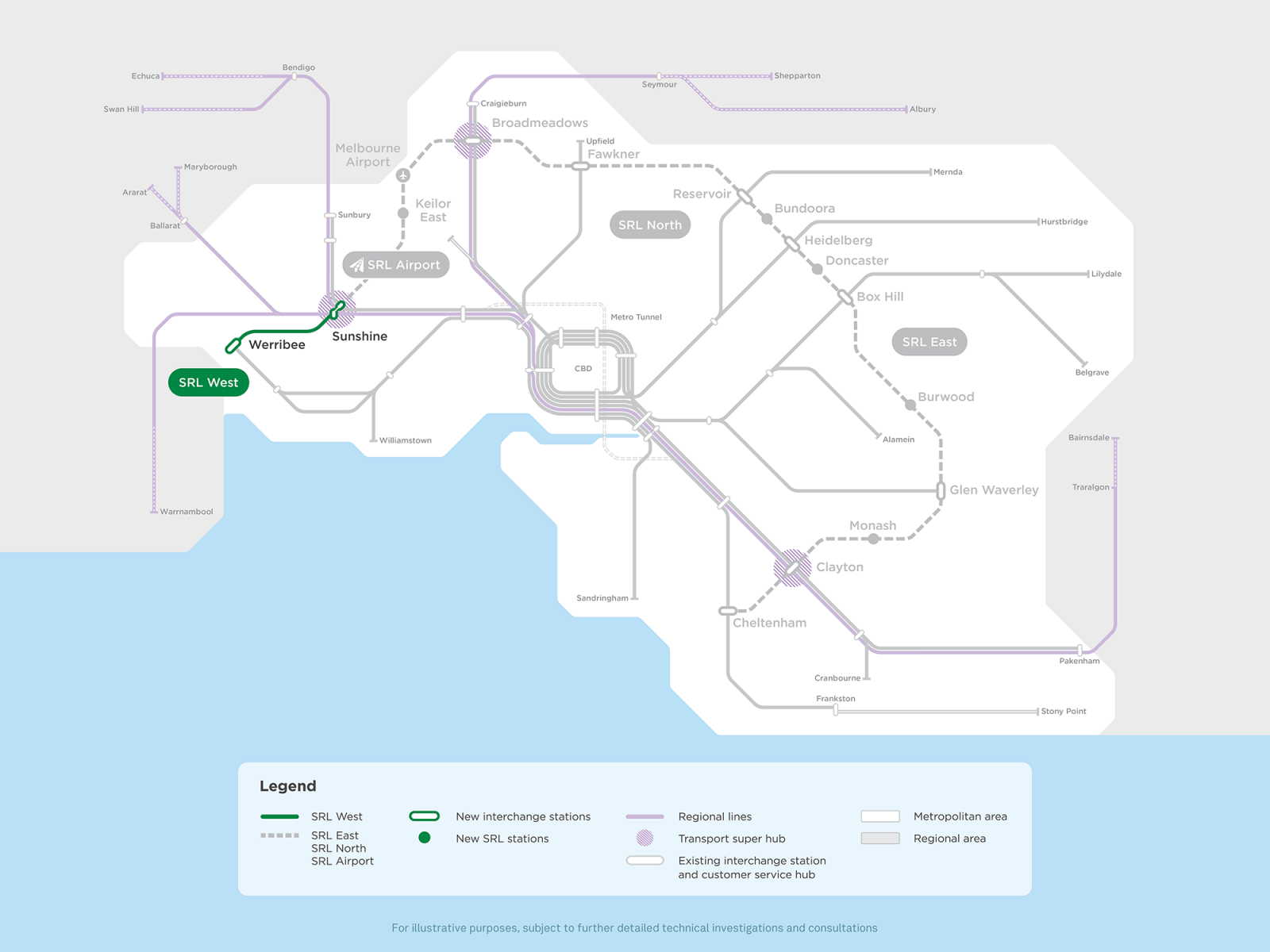

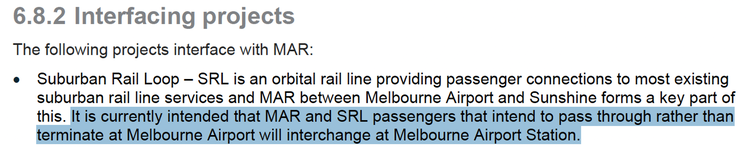

It considers the project as part of the Suburban Rail Loop initiative.

The Suburban Rail Loop project is a 90-km-long peripheral connector semi-circle line, spanning from Cheltenham to Werribee.

SRL East, currently under development, is being conceived as a driverless metro, a technological equivalent of Sydney Metro, which is technically incompatible with the conventional rail technology of Melbourne Metropolitan Trains.

The Airport connection of SRL belongs to SRL North and SRL West, and the latter is planned to continue onwards to Werribee via Sunshine, where a super-hub will be located. The most direct alignment between the Airport and Sunshine is the same alignment Melbourne Airport Link is expected to follow.

This poses a conflict between two technologies covering the same alignment which will need to be resolved.

Melbourne Airport Rail business case makes a quick reference to this problem by suggesting everyone travelling through Melbourne Airport alongside SRL will have to change trains there.

This is not an insignificant consideration both in terms of costs and accessibility outcomes.

Firstly, this means there will have to be two stations built in the Airport, one for the Melbourne Airport Rail and one for SRL.

Secondly, it is unclear how exactly SRL, or whatever it is in its place West of the Airport, is supposed to go past Sunshine to reach Werribee. If we assume SRL trains stop at the Airport, and people change to Metropolitan Trains services to continue onwards, this can mean two things.

Either there will be a train service that runs from the Airport to Sunshine, changes direction, and proceeds via Geelong Fast Rail and the planned new curve that will have it connect to Werribee, or, which is easier in terms of operations and feels as a more likely outcome, people will be expected to change trains at Sunshine—that is, changing trains twice on the way from the North to the West.

This means, changing trains twice between SRL North and Werribee, and changing trains thrice for anyone who isn’t on the SRL but is using SRL as an orbital connection between the Outer North and Outer West.

There is a profound lack of systemic vision here, and both projects do not seem to be tackling this well.

Through-running has never been properly considered.

The Business Case, and the preceding 2012 and 2018 studies, have given no consideration to through-running. All 21 options that went into shaping the present project consider Airport station being a dead end.

The ability to extend the line further North is only mentioned once, in the functional requirements in 2012 study. As demonstrated above, this is an extremely important service planning consideration that has been omitted with no further analysis provided.

Through-running is important, as it allows building a more connected network that goes to more places, thereby expanding the region-wide accessibility which is key to increasing the overall usefulness of public transportation and, consequently, its patronage. Dead-ending, to the contrary, limits the usefulness of the new service to the needs of accessing the airport alone.

Sydney and Perth have brought through-running into their airports. Overseas, there are many airports that enjoy multiple layers of through-running train services, including regional and high-speed trains. Most notable examples include Paris Charles de Gaulle CDG (high-speed rail services, national and international connections), Copenhagen Kastrup CPH (international regional services between Denmark and Sweden, including the cities of Copenhagen and Malmö), Amsterdam Schiphol AMS (regional and high-speed rail, national and international connections).

The Melbourne-Sydney-Brisbane high-speed rail project must be taken into account seriously, as well, with a direct interchange between planes and trains is extraordinarily beneficial by reinforcing the network connectivity at regional, national, and international levels in all of the examples above.

In 2018, a bolder Airport Rail vision that involves through-running regional rail connections has been produced by Australia’s Rail Futures Institute.

By establishing a new regional train line running through the airport and furtherly continuing to Seymour and Bendigo corridors, not only have they increased the regional connectivity of Tullamarine Airport but also essentially addressed the problem of running mixed Metropolitan and Regional rail traffic in Craigieburn and Sunbury lines, which represents considerable speed and capacity constraints.

Quadruplification of either of these lines, one that would allow giving each of these types of services their own pair of tracks, similar to what was delivered by Regional Rapid Line between Southern Cross and Sunshine, is extremely hard if not impossible to deliver due to the lack of available space within the present right-of-way.

The consideration of network-wide effects and region-wide network connectivity in 2012 and 2018 studies was severely limited, to the point of being barely mentioned, even though one of the reasons the Sunshine route is being pursued is exactly to gain the region-wide connectivity benefits.

The Business Case and its preceding studies lack accessibility analysis.

Apart from the year 2031 accessibility analysis for the preferred option (one executed incorrectly, as previously demonstrated), there is little information available with regards to the region-wide accessibility gains and losses, even for the four short-listed options.

By cutting further 10 minutes off the travel times, the more direct Maribyrnong route option would have also increased the accessibility gains for everybody coming to the airport from the CBD and the South East—which is, and, for obvious spatial reasons, will remain the vast majority of the airport’s users, passengers and employees alike.

Spatially, Melbourne is extremely large comparing to almost any other city of its population. Most of Melbourne’s South East is actually far away from everything. Pakenham line takes way over an hour to complete, and a one-way trip to Tullamarine would take more than an hour for anyone living beyond Clayton.

For a something like a 90-minute trip one-way, does it matter whether we take out from it 7…8 or 15…20 minutes?

To me, this difference is considerable, especially when we are talking $10bn worth of investment.

If we believe the whole project is needed to deliver region-wide accessibility benefits, it’s hard to understand that this analysis has not been presented or evaluated. This is a critical bit of information needed for the informed decision-making around the problem. We can’t be hiding it under the carpet.

Part 6 | What I think needs to be done.

At this point, I believe, the course the Melbourne Airport Rail project is taking needs to be re-evaluated, and—if not changed, then—adjusted.

The Melbourne Airport Rail Business Case must be updated, and the project justification re-affirmed.

The Business Case needs an immediate update.

Eliminate the nonsense: the methodologically and/or factually incorrect information needs to be removed. Anything that is by now outdated must be appropriately accounted for and updated.

Run the benchmark: an overview of costs and benefits of the comparable Australian and overseas projects needs to be done and included in the study. It is of paramount importance that Melbourne gets a project that is sensible and world-class, at the costs that are on par with the national and global experience.

Produce a holistic high-level rail vision for Tullamarine Airport: there must be a vision of what happens to the rail network while the project is being delivered, immediately after it is delivered, and for the target year 2056.

The current plans and the progress on them need to be consulted (such as the ways SRL and Melbourne Airport Rail are to work together), and all the ideas that are currently on the table, such as the High-Speed Rail project, need to be reflected and regarded in the planning.

Re-examine the options: in line with the requirements to the project set in 2012, it is of paramount importance that options are re-visited and additional options (mainly the ones involving through-running and/or regional rail connections) are explored.

Accessibility analysis for all the options involved must be produced. If Sunshine route is indeed the most reasonable route option to pursue (in its current or any other form), we must have it clearly proven, and have a clear justification for why it is so. The analysis must be done not only for the project alone (with reasonable minor adjustments alongside it taken into consideration, such as changes to the bus network) but also for the long-term visionary network. This may or may not need to be based on VITM.

Understand the costs: the project is currently overly expensive and is experiencing difficulties in delivery commencement despite everyone involved having committed the generous levels of funding. This must be understood, and the ways the costs may be considerably cut must be immediately explored.

This may need to become an additional study that must be delivered before the construction of the project is commenced. Australian experts and the engineering firms behind all other similar Australian projects must be involved and consulted in pursuit of these answers.

The Transit Costs project expert group, the world’s leading research collective studying costs of public transport projects delivery globally—in pursuit of taking the public transport costs under control in Canada and the US—may need to be invited to act as independent experts.

It is also my opinion that there is no reason for hiding the high-level cost assessments behind the ‘commercial-in-confidence’ wall of secrecy where public money is involved.

These updates are perfectly deliverable within no more than 12 months from now.

The total commitment to this project across State and Federal Governments is currently estimated at $10bn.

It is highly likely that there might be an opportunity to get much more for the amount in question, or to diminish the funding requirements for the currently preferred option whilst maintaining the benefits. These scenarios must be identified and explored.

Even a quick overview of the Australian experience of delivering similar projects to date shows that this is a lot, and there is a considerable potential in bringing this number down and releasing this money for other projects that are pending, including the very much needed public transport service level improvements throughout the entire region.

This should not be ignored. It may be reasonable to take the courage to revise the plans if doing so in the present realm is identified as sensible. Until the contracts are committed to, and the shovels hit the ground, it is not too late to do so.

An up-to-date business case is, in my opinion, an appropriate tool to help with this.

In the meantime, there’s no need to keep waiting another decade to have the Tullamarine Airport’s public transport accessibility improved. It can and must be done now.

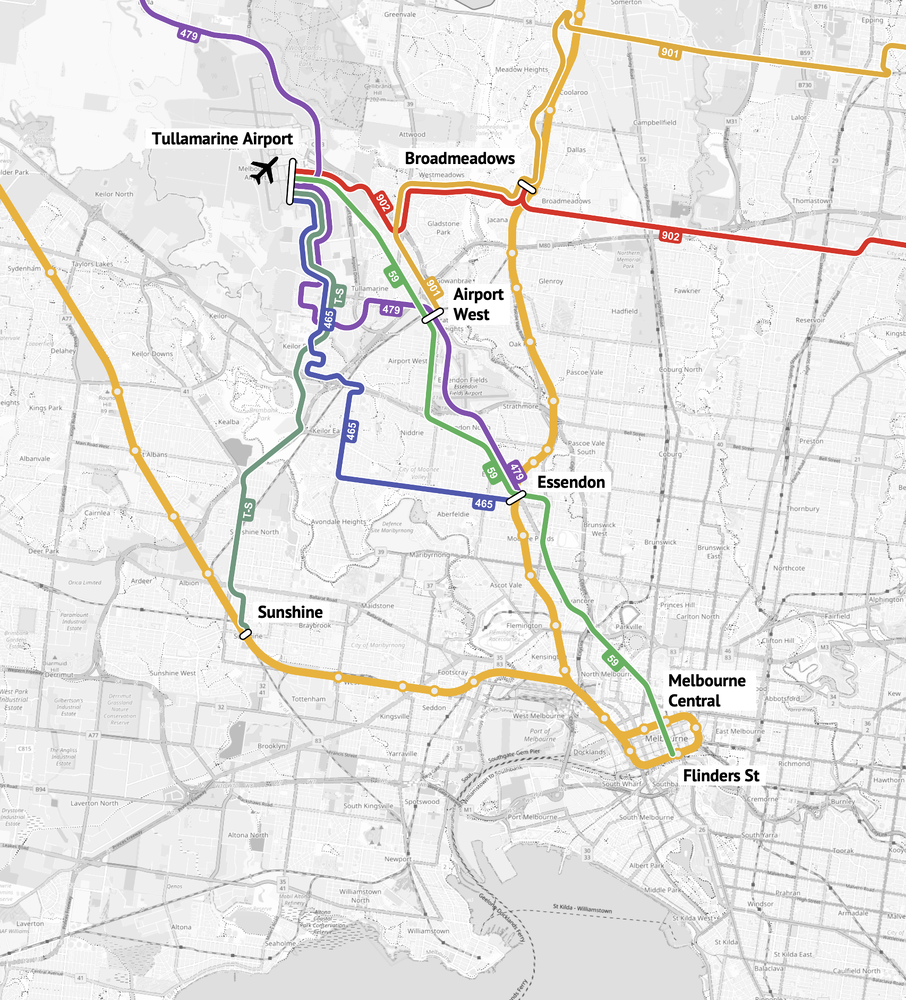

Part 7 | How to dramatically improve Tullamarine Airport’s accessibility by public transport, now

The Melbourne Airport Rail makes recognition of the airports’ public transport services’ deficiencies.

A lot of those can be fixed instantaneously with a very simple and extremely affordable solution: buses.

As the public transport network around the Airport is extremely limited in coverage, frequency, and span (except bus 902), there is no available zero-cost optimisation that would lead to improved outcomes through reshuffling the available buses or adjusting the network. Additional services are necessary.

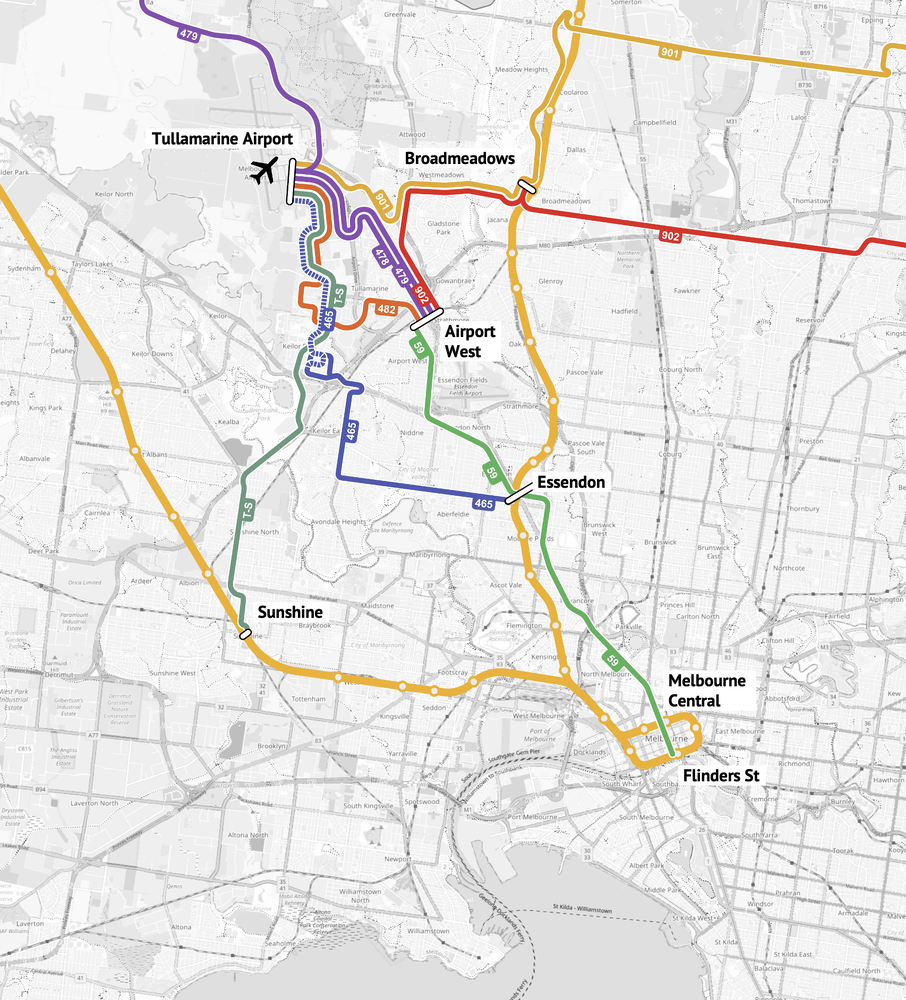

I suggest the following changes to the bus network around Tullamarine are introduced to address the most pressing accessibility issues of Tullamarine Airport:

Step 1. Create a direct route between Tullamarine Airport, Keilor Park, and Sunshine.

Melbourne Airport Rail is purposefully traced through Sunshine which is defined as a destination sufficiently important for this to be the case. This is driven by the idea of developing Sunshine as a ‘super-hub’, and the regional transport connections already available there. Sunshine is also one of the least accessible places from the Tullamarine airport, overall, despite being relatively close to it.

There is no reason why there isn’t a public transport service that connects Sunshine to Tullamarine right now, as well as there is no reason why we should wait a decade for one to be established by Melbourne Airport Rail.

A reasonably frequent bus service needs to be established.

Step 2. Extend route 465 from Keilor Park to Tullamarine Airport (including the frequency/span uplift).

This extension would:

· Provide direct connections to the nearby suburbs of Keilor Park and Keilor East (including the area around the envisaged new Keilor East station),

· Improve the local connections in the employment area South of airport (one that is currently served by a local 482 bus that runs 8 times a day, weekdays only).

· Provide a single-seat connection to Essendon station which currently doesn’t exist.

Step 3. Extend routes 478-479 to Essendon Station directly (including the frequency/span uplift).

This extension would:

· Eliminate the need for changing at Airport West between the trams and the buses and provide the most direct single-seat connection possible between the Airport and Essendon station, thereby making the latter the primary interchange on the way to the airport, instead of Broadmeadows, and saving the customers a considerable amount of time.

This may be done with the buses running along Tram 59 (with all stops through Essendon North, similar to Bus 477) or, alternatively, via Bulla Rd and DFO Essendon, furtherly running express via Tullamarine Fwy between and Airport West.

Step 4. Send Bus 902 to the Airport (swap with 901).

A direct connection to the airport from the corridor of Camp Rd and Mahoney Rd would be beneficial to people across a wide range of populated and growing suburbs of Bundoora, Reservoir, Fawkner, and even Preston, including by allowing a more reasonable combination of train and bus with one change only.

Such a connection may be introduced at near-zero cost by swapping 902 and 901 in their Westernmost ends (i.e. by sending 901 to Airport West and 902 to the Airport).

For anyone travelling between Broadmeadows and Airport West, or Broadmeadows and the Airport, this will only result in having to take the bus with a different route number. Outside of that specific stretch, some people who don’t need to change buses presently will need to change buses at Broadmeadows.

While this would bring in some inconvenience to some customers, overall, connecting the Airport directly with the suburban corridor that is denser, better connected, and allows for a more linear service seems to be a reasonable thing to do.

Compared to the $10’000 million Melbourne Airport Rail project budget, all changes described above can be delivered together at under $20 million per annum for the service, including the frequency/span uplifts which would provide the frequent bus service in the Airport early morning till midnight, seven days a week.

It is hard to see why this can’t be delivered next Monday.

A longer-term vision may include extending Tram 59 to the Airport, which would furtherly improve the local connectivity between Essendon and the Airport.

The costs of the most recent tram network extensions gives us the idea around the capital costs of such an extension, which, as a direct extrapolation, appear to be under $60 million, although with all similar projects being well pre-COVID, this number may need to be doubled.

The additional tram operating costs would be around $11 million per annum.

(However, it would also effectively substitute bus 478 which, in its previously suggested extended and enhanced version, would cost about $6 million per annum to run, hence the overall increase would be around $5 million per annum.)

Such an extension would be a logical development of the tram network, as Tullamarine Airport is clearly a more important destination than Airport West.

Whether it is worth the investment required may still be open for interpretation, however, I would be inclined towards doing it—not for the monetary reasons, but—for the network effects, for the reputation of trams (which Melburnians are extremely proud of, not without a reason!), and for the fact much less popular destinations have their trams already in place for the similar reasons, such as Box Hill.

(Side note: I would also apply a similar logic to several other potential moderate tram network extensions to be done in pursuit of reaching a nearby large-scale destination, such as extending 48 to Doncaster.)

All public transport improvements outlined above can be delivered much sooner than the Melbourne Airport Rail project, allow to gain many of the benefits of the latter, sooner, and will be complementary to Melbourne Airport Rail once it’s complete and running.

Conclusion

Melbourne Airport Rail project in its current form lacks strategic vision.

A major part of the reasoning behind the project seems to be based on a long-term traffic projection that may or may not materialise.

The project appears to be delivering insufficient benefits when compared to the present day’s performance of the citywide transportation system, including public transport. The costs for such a project being payable now, and the benefits being largely conditional and only gainable much farther in future, may not be the most reasonable approach in ascertaining the project viability and making decisions around its delivery.

Its benefits may not have been accurately articulated, and sometimes may not have been properly assessed, due to limitations or flaws in the methodology and the analysis, including some of the reasonable assumptions (such as possible changes to the bus network around Sunshine, or possible introduction of bus lanes for the current Airport bus services) having been omitted (regardless of the reasons and decisions that may have led to such omissions).

The costs for delivering Melbourne Airport Rail are way higher than the ones for any of the comparable Australian projects, including the most recently delivered Forrestfield-Airport link in Perth, which Melbourne Airport Rail, as the best case, exceeds in capital costs by a factor of four.

This kind of a difference is not only definitive to the overall project’s benefit-cost ratio but also to the overall costs of public transport project delivery which, if allowed to increase at such a scale, may make future projects undeliverable.

It is therefore important to be able to independently ascertain why exactly this project is so expensive. It is incomprehensible that the high-level cost assessments are not readily available to the public and remain ‘commercial-in-confidence’ where the governments’ funding commitments have long been announced.

At the same time, it appears that some of the key benefits can be gained through delivering moderate public transport service improvements, most of which can be rolled out as soon as next Monday and require an extremely moderate (almost negligible compared to Melbourne Airport Rail) upfront investment.

This includes establishing a frequent bus service between Tullamarine Airport and Sunshine station, the lack of which is among the key reasons why the Melbourne Airport Rail project is envisaged as going through Sunshine. That being said, both said service needs to be established, and the accessibility benefits of Melbourne Airport Rail project, in its current form, re-assessed with this service in mind, among other considerations indicated throughout this article.

The limited public transport access in Tullamarine Airport is a problem that affects customers and employees alike and is broadly recognised as such.

When the builders of the Airport Rail (in whatever its form) first reach the construction sites, it would take up to a decade before the Airport trains begin running. There is no reason to keep waiting that long before many of these issues are—if not solved, then—considerably mitigated.

And before the construction begins, it is not too late to revise the plans and come up with new, revised and improved plan for the Melbourne Airport Rail project.

Sources

- Melbourne Airport Rail Business Case. — Victoria’s Big Build, State Government of Victoria, Australian Government, September 2022. https://bigbuild.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/710179/MAR-Business-Case-Main-Document.pdf

- Melbourne Airport Rail Business Case Supplement. Keilor East Station. — Victoria’s Big Build, State Government of Victoria, Australian Government, September 2022. https://bigbuild.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/710180/MAR-Business-Case-Supplement-Keilor-East.pdf

- Melbourne Airport Rail Link Alignment Alternatives Study. Volume 2: Technical Report Final. — Public Transport Victoria, Parsons Bricknerhoff Australia Pty Ltd, December 2012. Accessed via Under The Clocks Blog: https://undertheclocksblog.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/melbourne-airport-rail-link-study-technical-report.pdf

- Melbourne Airport Rail Link. Sunshine Route. Strategic Appraisal. — Transport for Victoria, 2018. https://bigbuild.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/397706/MAR-Sunshine-Route-Strategic-Appraisal.pdf

- Melbourne Rail Plan. — Rail Futures Institute, 2019. https://www.railfutures.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/15329_MRP2050main_FinalPages.pdf (specifically section 5.7)

- Suburban Rail Loop Business and Investment Case. — Suburban Rail Loop Authority, Victoria’s Big Build, State Government of Victoria, August 2021. https://bigbuild.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/578281/SRL-Business-and-Investment-Case.pdf (specifically maps from the Executive Summary)

- How much does public transport cost to run? — Melbourne On Transit, 2024. https://melbourneontransit.blogspot.com/2024/05/un-173-how-much-does-public-transport.html

- Song about Melbourne by Gillian Cosgriff: https://www.instagram.com/p/C5R4i7CPvjt/

- Screenshots from Apple Maps used for illustrative purposes only. Own maps produced with OpenStreetMap base.

I extend my deepest gratitude to every person who has been kind enough to dedicate their time and discuss the Melbourne Airport Rail project with me to help me understand its history and context as I was preparing this article.