I recently found myself fossicking through the sand for bits of old submarine telegraph cable (The All Red Line).

Direction Island, part of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands chain, sits in a lonely expanse of the Indian Ocean, an outpost of Australian territory that guards waters to Asia. A museum specialist had told me that pieces of cable were there, scattered among the tide pools – fragments of telegraph lines that once carried dots and dashes of Morse code and connected the British empire.

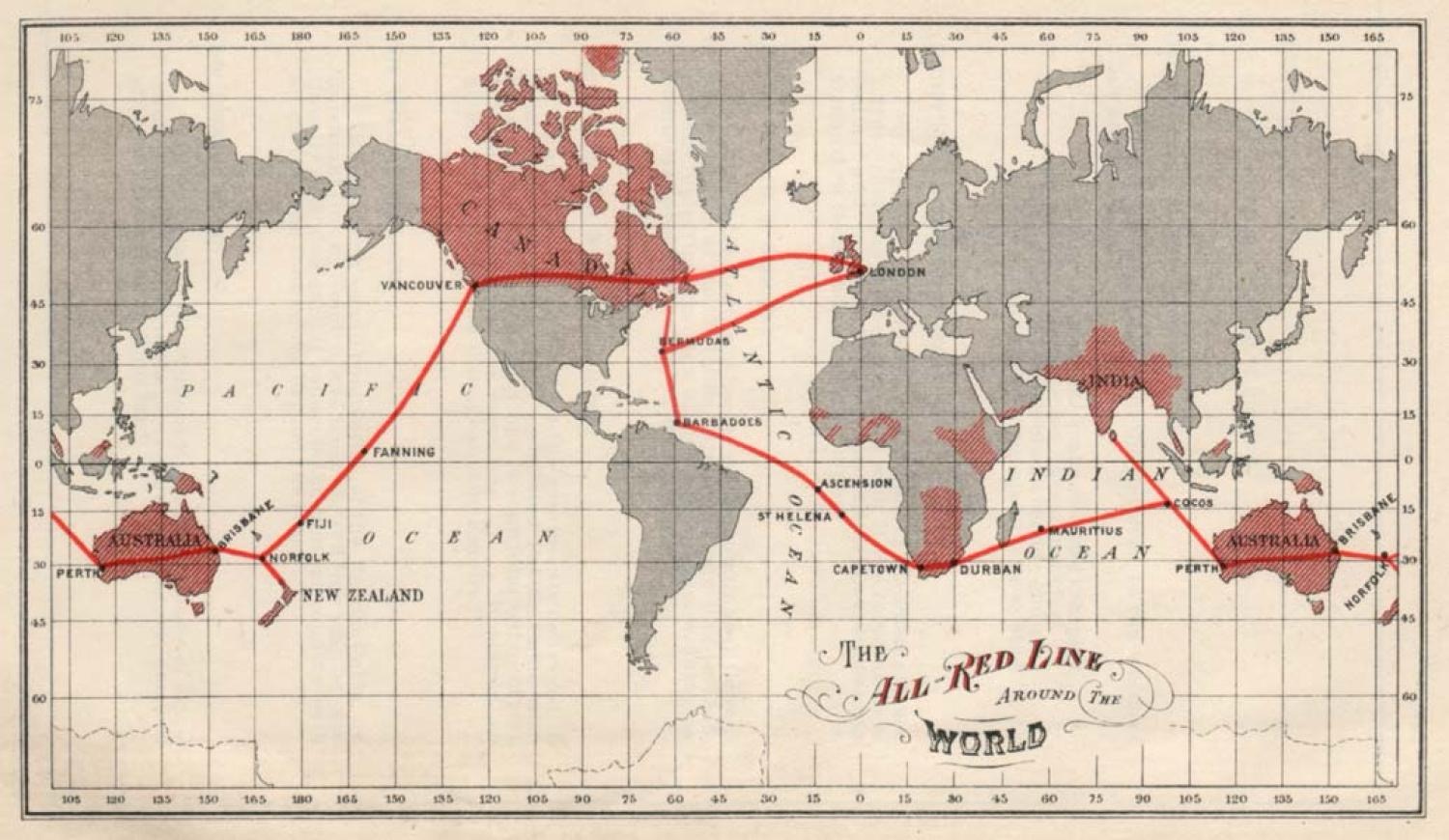

The All Red Line was a system of electrical telegraphs that linked much of the British Empire. It was inaugurated on 31 October 1902. The informal name derives from the common practice of colouring the territory of the British Empire red or pink on political maps.

When I eventually discovered a piece of this fading history, I was struck by its weight. The rusted metal sheath of the cable was hollow, heavy and encrusted with coral. It looked ancient, discarded. The cable I held was laid during Australia’s first decades as a federated nation, part of Britain’s global communications web.

Around me, 20 day-trippers splashed in the shallows, snorkelled and spread towels on the sand. They’d come for the famous Direction Island beach – voted Australia’s best stretch of sand back in 2016. My silent search for remnants of Britain’s subsea information highway must have seemed quaint.

But this history matters. The world is again focused on undersea cables, essential conduits of the digital age. From the 1900s to the 1960s, Direction Island was a critical node in the “All Red Line” – the British Empire‘s submarine telegraph cable network that linked London to its colonies, designated red on maps, demonstrating imperial reach. Forgotten nodes like this will be critical again in the modern era of strategy and data connectivity.

Let’s not forget the critical telegraph line that linked Adelaide with Darwin in the late 1800’s called the overland telegraph line. This line connected Australia on the north south route and connecting with the subsea cable between Darwin (Palmerston) and Java allowed for the first time Australia to send and receive overseas communications via under sea cable.

An island that struggles with irregular flights and delayed supply ships is set to become a digital nexus, a place where vast streams of data will flow even as basic logistics remain fragile.

A balustrade from the old cable station rusts on the beach. I’d seen another similar structure at the Cocos Islands museum a day earlier, neatly preserved. Finding this one abandoned felt eerie. The buildings that once housed 50 or more telegraph workers have long since been demolished. The island has returned to jungle, dense and overgrown. I thought about venturing further to search for other remnants, but the mosquitoes were unrelenting.

In the 1960s, the cables on Direction Island went silent as the station closed. For decades, Direction Island became just another uninhabited speck in the Indian Ocean, visited by tourists but otherwise left to the crabs and seabirds.

Australia acquired its Indian Ocean Territories from Britain in the 1950s – the Territory of Christmas Island in 1958 and the Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands in 1955. Not part of any Australian state, these islands are administered directly from Canberra, with the Commonwealth Department of Infrastructure responsible. Despite this, Western Australian law applies, and residents vote in the federal electoral division of Lingiari – which otherwise comprises the entire Northern Territory, besides Darwin. It’s a curious status, and you feel it immediately upon arrival.

Flying hours across the empty and vast Indian Ocean from Perth, the islands feel genuinely remote. Weather can play havoc with flight schedules and bags are often left behind due to strict weight restrictions. Supply ships regularly run late. There’s a sense of logistical fragility, of being tethered to the mainland by thin threads of infrastructure.

The yellow “international” arrival cards passengers must fill out – otherwise not required on domestic flights – signal that this isn’t the usual Australian destination. Federal police patrol both islands, another reminder of the territories’ unique constitutional position. The architecture is different, shaped by decades of extraction economies – whether phosphate or copra respectively. It’s a peculiar mix: undeniably Australian, yet distinctly unique.

I arrived on Christmas Island just as the red crabs began their annual migration. Millions of them, moving from the rainforest to the sea, following rhythms older than any human settlement. They blanketed the roads (and the purpose-built crab bridge) – oblivious to the cars carefully navigating around them.

Christmas Island is positioning itself for a post-phosphate mining future. The mine has been the island’s economic backbone for more than a century, but the community is looking ahead to what comes next. Tourism is one option. Digital infrastructure, it turns out, might be another.

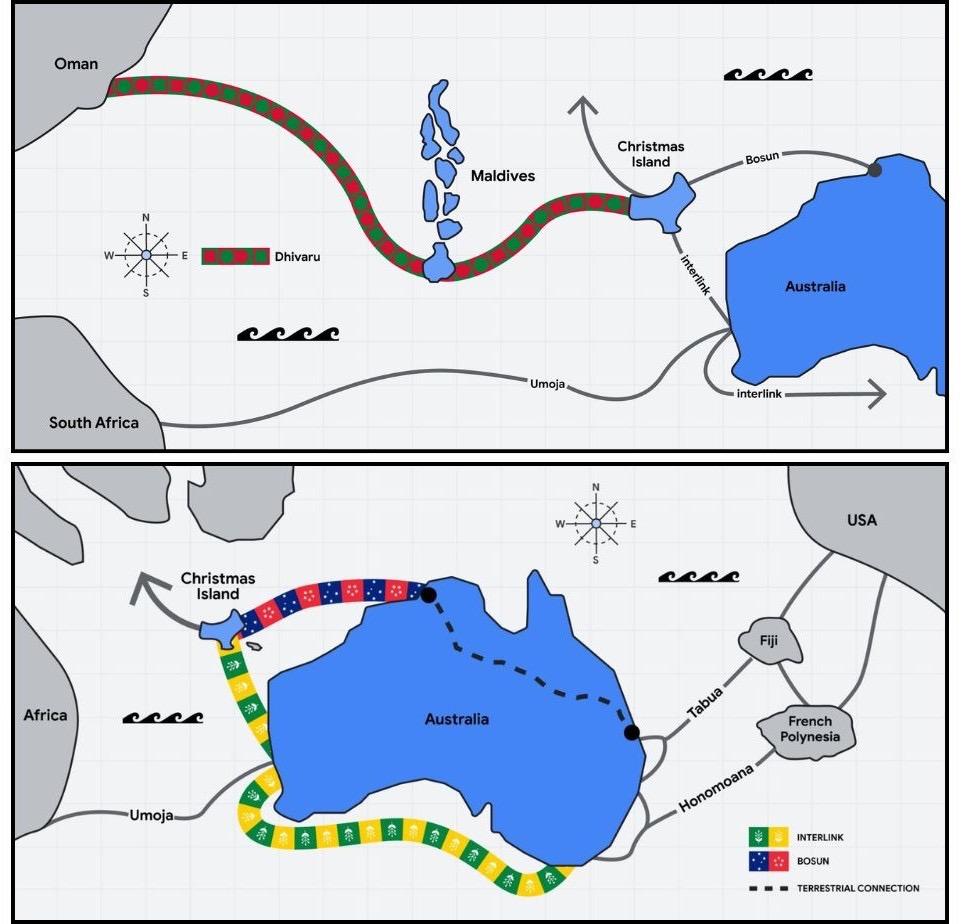

Google is in advanced talks to build a data centre on Christmas Island and land several new fibre optic submarine cables on the shores. The project follows a cloud computing agreement between Google and the Australian Department of Defence signed earlier this year, according to a Reuters report. Multiple new submarine cable systems are planned, potentially making this tiny island of a little more than 1,600 people into a hub for Indian Ocean connectivity.

The island is accustomed to reminders that geography shapes destiny.

Somewhat ironically, an island that struggles with irregular flights and delayed supply ships is set to become a digital nexus, a place where vast streams of data will flow even as basic logistics remain fragile. Google has committed to using renewable energy, which locals appreciate, though the reality is that Christmas Island remains heavily dependent on fossil fuels.

For locals, the response is cautiously optimistic but laced with uncertainty. Will this project genuinely benefit the island’s economy, or will Christmas Island simply be a bypass point, a convenient piece of geography for a global infrastructure project? The questions reflect a deeper tension: how to balance local needs against national interests in a strategically located territory?

The Australian Border Force vessel Ocean Shield was just offshore when I visited, and Border Force is a persistent presence on Christmas Island. The island sits just 350 kilometres south of Java. People smuggling is a persistent issue. The controversial immigration detention centre that has featured so prominently in post-2001 Australian politics sits on high readiness, although currently empty, now managed by an American private prison operator. The island is accustomed to reminders that geography shapes destiny.

On Cocos (Keeling) Islands, similar dynamics are at play. The islands were connected to the global internet with fibre in 2022 via the Oman-Australia Cable, ending years of relative isolation after the Direction Island cable station was shuttered in the 1960s. Now there are rumours of more submarine cables to come.

But cables aren’t the only infrastructure arriving. The military is upgrading the airfield on Cocos, with enabling construction underway at the port – works that have prompted concerns among residents. Is Canberra being honest about the eventual use of these facilities? Will Cocos be drawn into future regional conflicts?

These aren’t abstract worries but are rooted in history.

Monuments on Cocos commemorate attacks during both world wars. On Direction Island in Cocos, a memorial marks the 1914 raid by the German light cruiser SMS Emden, which destroyed cable station infrastructure before being engaged by HMAS Sydney in one of the first naval battles involving an Australian warship. In the Second World War, Direction Island was shelled by the Japanese. In both cases, the islands mattered precisely because of their strategic location and communications infrastructure.

HMAS Sydney, named for the Australian city of Sydney, was one of three modified Leander-class light cruisers operated by the Royal Australian Navy. Ordered for the Royal Navy as HMS Phaeton, the cruiser was purchased by the Australian government and renamed prior to her 1934 launch.

Construction on the Cocos airfield hasn’t started yet, but when it does, it will be disruptive to local life. During my visit works were centred around port upgrades, enabling works for the larger project. Locals are readying themselves for the construction to commence in earnest and are weighing the possible economic opportunities against the strategic implications.

While I took some cable fragments from Direction Island, I left other pieces of rusting history among the coral for others to find. Now administered as Australia’s “Indian Ocean Territories”, Christmas and Cocos islands still play an outsized role in strategic calculations – made now in Canberra rather than London. Sitting astride critical sea lines which link continents, perhaps the fate of these unique islands hasn’t fundamentally changed since the days of the All Red Line.

the interpreter article used as the basis of this article